Nephrotic syndrome is a rare kidney condition that occurs in about five in 100,000 children worldwide. It is diagnosed when proteinuria (high levels of protein in the urine), hypoalbuminemia (low levels of albumin in the blood), and edema (swelling) are all present together in the body. Most children with nephrotic syndrome get better with treatment and experience no long-term kidney problems.

What is nephrotic syndrome?

Proteinuria

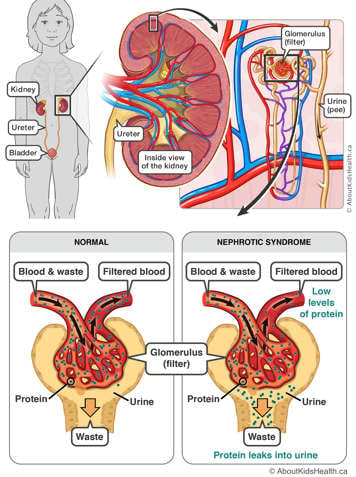

Proteinuria is when there are high levels of protein in the urine. Normally, there is little to no protein found in urine. In nephrotic syndrome, the glomeruli (the filters within the kidney) leak protein from the blood that flows through them into the urine they produce.

Hypoalbuminemia

Hypoalbuminemia is when low levels of protein (albumin) are found in the blood. When a large amount of protein leaks out into the urine, the body cannot make enough new protein to keep up. This results in hypoalbuminemia.

Edema

Edema happens in nephrotic syndrome because of low protein levels in the blood. Protein normally acts like a sponge to keep fluid in the blood vessels. With less protein in the blood, fluid leaks out of the blood vessels into other tissues. Edema is typically seen around the eyes, face and legs. Fluid can also build up in the abdomen, around the genital area or in the lungs.

Signs and symptoms

When a child first presents with nephrotic syndrome, they may be irritable and have swelling around the eyes, abdomen, lower legs and sometimes the genitals.

You may also note the following changes in your child:

- Weight gain because of fluid retention

- Less frequent urination (peeing) or foamy urine

- Abdominal pain or discomfort

- Diarrhea (loose stools) and/or vomiting

- Feeling generally unwell and tired

Causes of nephrotic syndrome

Most nephrotic syndrome in children is idiopathic, meaning that the cause of nephrotic syndrome is unknown. Nephrotic syndrome is more common in boys than girls, and often appears for the first time in children under five years of age.

The most common types of nephrotic syndrome in children are minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).

Rarely, some patients have nephrotic syndrome in the first few months of life. In these cases, the cause is most likely genetic, meaning that the glomeruli did not develop normally before birth.

Course of nephrotic syndrome

For childhood nephrotic syndrome, most patients respond well to treatment with a steroid medication called prednisone or prednisilone. About 80% of children will improve with steroids. Even with successful initial treatment, some children with nephrotic syndrome can have relapses. Treatment plans for children with relapses are customized based on whether the child has frequent or infrequent relapses. Prognosis is excellent—the majority of children, especially those with minimal change disease, will outgrow nephrotic syndrome and become adults with normal functioning kidneys.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by testing the urine for proteinuria, and the blood for hypoalbuminemia, in the presence of edema. The disappearance of protein in the urine after the use of prednisone helps to confirm the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome. Sometimes, the doctor may also recommend a kidney biopsy to help with the diagnosis and treatment of nephrotic sydrome.

Treatment of nephrotic syndrome

The goal of treatment is to stop the kidneys from leaking protein into the urine. The initial treatment of nephrotic syndrome is with prednisone or prednisilone, which is taken every day for at least six weeks and then slowly decreased over several months. Steroids work in many different ways for nephrotic syndrome, but the exact way they work is not known. It is important to continuously take prednisone as instructed without stopping suddenly. Sometimes, this first course of treatment is all that is needed. However, for some children, the disease can return, which requires further treatment.

Prednisone usually works very well to treat nephrotic syndrome. Most children respond to prednisone; however, a small number of children do not. In these cases, a kidney biopsy may be required. Some children may need to take other medications that suppress the immune system, such as cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, mycophenolate or rituximab.

If there is severe edema, your child may need to be admitted to the hospital to receive protein (albumin) intravenously. Your child may also be given a diuretic (“water pill”) to help remove some of the extra fluid that has accumulated in the body. It is very important for a child with nephrotic syndrome to eat a low-salt diet to prevent fluid retention. Consuming more protein in the diet will have no effect and is not recommended. While on prednisone, it is also important to eat a low-salt and low calorie diet.

While on steroid medication, your child is at higher risk of infection. Seek immediate medical attention if your child shows signs of fever or other signs of infection. Let your dentist know that your child is on steroids, and speak to your health-care team before giving any vaccinations.

Prevention of complications

- Always give medication as directed by your health-care provider.

- It is important to regularly monitor your child’s urine.

- Adhering to a low-salt diet during a relapse also helps control symptoms.

Complications

Hyperlipidemia (high levels of blood cholesterol and triglycerides) is a common consequence of nephrotic syndrome. If albumin levels are low due to leakage, the balance of various fats in the body is altered, which leads to high levels of cholesterol. This is usually temporary and does not cause long-term harm, as cholesterol levels normally re-balance with treatment.

If nephrotic syndrome is left untreated, complications such as infection, fluid overload (significant swelling causing discomfort), kidney injury and blood clots can occur.

Your role as a caregiver

It is important for you to monitor your child’s urine for protein because it is the first sign of a relapse. Your health-care provider will teach you how to check your child’s urine with a dipstick. You will need to check the first sample of urine every morning and report back to your health-care team if the dipstick tests positive for protein (anything greater than ‘trace’ amounts [greater than 0.3 g/L]). Your health-care provider may recommend keeping a bathroom scale at home to look for sudden changes in weight.

How to test urine for protein with dipsticks:

- Collect first morning urine into a clean container.

- Take one strip out of bottle, and close bottle tightly.

- Dip the strip into the urine quickly. Be sure the square on the tip is wet with urine.

- Place the strip on a flat surface and wait 60 seconds.

- Compare the colour of the stick to the colours on the bottle.

- Record the value: the packaging should show you which range(s) indicate “normal.”

If the dipstick results show as above the “normal” range (0.3 g/L or higher), contact your health-care provider.

Note: Always check the expiry date of the dipstick bottle. Be sure to test the urine while it is fresh (within one hour). Ensure that the dipsticks are stored in a cool, dry place and that the bottle remains tightly sealed. Do not store dipsticks in the kitchen or bathroom.

Long-term outcomes/future expectations

Most children respond well to treatment and have a good outlook. Nephrotic syndrome rarely causes kidney failure and children are likely to grow out of it. It is not uncommon for children to have at least one relapse. If your child has a relapse, they will receive repeated treatment with prednisone or other medications. Sometimes, continuous low-dose steroids every second day and/or an additional medicine may be needed to stop relapses that occur too often.

When to call your health-care provider

- If your child has chicken pox, or has direct contact with someone who has chicken pox, while on prednisone.

- If urine becomes positive for protein again.

Take your child to the nearest emergency department if your child:

- is swollen

- is unwell with a fever

- has a persistent headache

- has vomiting or abdominal pain and/or decreased urine output

Resources

The Kidney Foundation of Canada (www.kidney.ca)

NephCure® Kidney International (www.nephcure.org)

References

Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome: A Guide for the Parents on the Management and Treatment of Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome. The Kidney Foundation of Cananda. Retrieved from https://www.kidney.ca/document.doc?id=330.

Downie ML, Gallibois C, Parekh RS, Noone DG (2017). Nephrotic syndrome in infants and children: pathophysiology and management. Paediatr Int Child Health, 37(4), 248-258.

Banh TM, Hussain-Shamsy N, Patel V, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Borges K, Sibbald C, Lipszyc D, Brook, J, Geary D, Langlois V, Reddon M, Pearl R, Levin L, Piekut M, Licht C, Radhakrishnan S, Aitken-Menezes K, Harvey E, Hebert D, Piscione T, Parekh RS (2016). Ethnic differences in incidence and outcomes of childhood nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 11(10), 1760-1768.