What are neuroinflammatory disorders?

Neuroinflammatory disorders are conditions in which the parts of the central nervous system (CNS) are affected by inflammation. The CNS is made up of the brain, spinal and optic (eye) nerves. The immune system is a cellular system that protects our bodies from infections and injury. Sometimes, the immune system can over-react and can cause inflammation by attacking healthy tissues in the body. This process is called ‘auto-inflammation’.

What are antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorders?

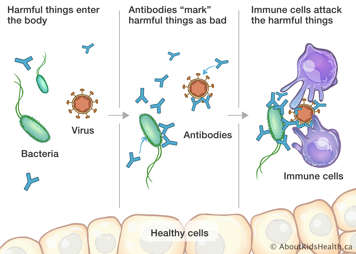

In antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorders, the body produces proteins called ‘auto-antibodies’ that act against the body's own structures. Antibodies are normally a protective protein produced by the immune system to stop intruders like viruses and bacteria from entering the body. An example of protective antibodies are ones that are made by the body after a vaccination to protect against the measles virus.

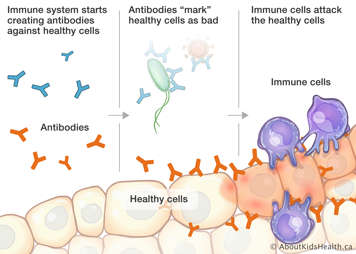

Auto-antibodies are abnormal antibodies, which are also produced by the immune system. Unfortunately, these antibodies attack the body instead of protecting it. When auto-antibodies attack the body tissues, this produces irritation and inflammation in healthy tissues.

Auto-antibodies directed at structures in the brain can lead to irritation and swelling of brain tissue called ‘encephalitis’. Inflammation of the optic nerves can cause optic neuritis, which causes blurry vision.

What happens when auto-antibodies attack the central nervous system?

When auto-antibodies attack the CNS, this causes irritation and inflammation in the brain tissue, which can produce symptoms of confusion and sleepiness. Other symptoms can include:

- Headache

- Seizures

- Difficulty walking or with balance

- Vision loss

- Memory loss

- Changes in concentration and behaviour

Inflammation in the brain can also cause psychiatric symptoms such as:

- Hallucinations

- Distortions in thought

- Confusion

- Mood swings

Neuroinflammatory disorders that are caused by an auto-antibody are relatively new conditions that were previously under-diagnosed. Recognition and awareness of these conditions is growing. The following information describes three currently known antibody-mediated inflammatory brain disorders: anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) and anti-MOG antibody-associated encephalomyelitis.

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is thought to be the most common antibody-mediated brain disease. In anti-NMDAR encephalitis, auto-antibodies target the NMDA receptor. This is a receptor which is found on the surface of brain cells called neurons. This receptor is very important for cell-to-cell signaling in the brain. The abnormal auto-antibody binds to the NMDAR site and reduces the number of available receptors on the surface of the brain cells. This causes abnormal nerve signaling, and the brain becomes swollen, leading to a condition called encephalitis. Encephalitis can lead to confusion, memory issues, behaviour changes and other symptoms.

It is not known what triggers anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis was discovered in 2007, initially in female adults. It primarily affects young adults and children, with a female predominance. In adults, the disease is more commonly associated with an ovarian tumour; however, this association is rarely seen in children.

What is the prognosis for anti-NMDAR encephalitis?

After anti-inflammatory treatments are given, patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis may continue to have symptoms for many weeks and often require inpatient rehabilitation to return back to their pre-illness state. It can take many months for children to be able to return to their regular activities. Fortunately, after immune suppressive treatments are given, the antibody stops being produced and symptoms often do not re-occur. Some children continue to experience disability or seizures after treatment; however, these complications can be managed with medications and therapies. Patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis are monitored regularly by a health-care team, which can include neurologists, psychiatrists and nurses.

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD)

In NMOSD, auto-antibodies target a receptor on the nerve cells called the aquaporin-4 water channel (AQP4). The AQP4 protein is important in maintaining brain water volume. When the AQP4 auto-antibody attacks this protein in the CNS (the optic nerves, spinal cord and brain), it causes inflammation, destruction of the channel itself and irritation of the surrounding nerve tissues.

NMOSD typically presents most commonly in middle aged adults but can be seen in children and seniors. In all age groups, NMOSD occurs more in females than males. NMOSD is most common in people who are non-Caucasian.

What is the prognosis for NMOSD?

There is presently no cure for NMOSD. The NMOSD antibody can be treated with medications that suppress the immune system. However, if the medications are stopped, the antibody will return and cause inflammation again. Fortunately, patients who take their immune suppressive medication regularly and maintain a healthy lifestyle can minimize relapses or reoccurrence of their disease symptoms. Patients with NMOSD are monitored regularly by a health-care team, which can include neurologists, ophthalmologists and nurses.

Anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody encephalomyelitis

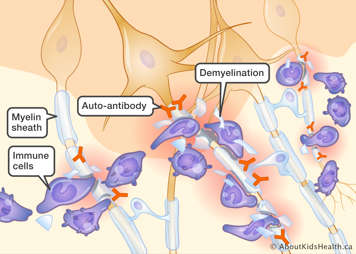

Anti-MOG auto-antibodies can also cause inflammation in the optic nerves, spinal cord or the brain. The anti-MOG antibody attacks myelin, a protective layer covering the nerve cell. Many of the fibers in the nervous system have a coating, called a ‘sheath’, of myelin covering them. The myelin sheath allows electrical signals (impulses) to pass along the nerve cells efficiently. If the myelin is inflamed or damaged, the nerve cells cannot communicate or function properly. This process is called demyelination.

What is the prognosis for patients with anti-MOG antibody encephalomyelitis?

Patients who have a one-time demyelination event and whose anti-MOG antibody later becomes negative have a good prognosis. These patients have a lower risk of having a second demyelination event. Patients who continue to have a positive blood test for the anti-MOG antibody are at higher risk of having additional demyelinating events. These patients often require longer-term treatment with an immune suppressant medication to prevent reoccurrences (relapses) of their illness. Patients who require longer-term treatment with immune suppressive medications and who maintain a healthy a lifestyle can minimize relapses or reoccurrence of their disease symptoms. If your child has anti-MOG antibody encephalomyelitis, they will be monitored regularly by a health-care team, which can include neurologists, ophthalmologists and nurses.

Signs and symptoms of anti-NMDAR encephalitis

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis can sometimes begin with viral type symptoms such as:

Children may then develop behaviour abnormalities, hallucinations, memory loss, speech problems, or abnormal facial or limb movements. In young children, the first noticeable symptoms can often be irritability or temper tantrums. This is likely because young children cannot communicate exactly what they are feeling. For many children, the first sign of this illness is a seizure.

Signs and symptoms of NMOSD

Since the AQP4 channel protein is located in the optic nerves, brain and spinal cord, symptoms of NMOSD typically occur in these areas of the body. The optic nerves are located in the eyes. Inflammation of the optic nerves is called optic neuritis. Optic neuritis can cause:

- difficulty seeing

- blurry vision

- eye pain or headaches

Inflammation in the brain can cause confusion, a change in sleep patterns or changes in level of consciousness. Often, the vomiting center in the brain can become affected. This produces symptoms of hiccups, nausea and uncontrollable vomiting.

If there is inflammation in the spinal cord, muscle spasms, weakness or numbness to the limbs can occur. Difficulty walking or going to the bathroom may also occur.

Signs and symptoms of anti-MOG antibody encephalomyelitis

Symptoms of demyelination depend on where the demyelination occurs.

- If demyelination occurs in the optic nerves, this can cause vision symptoms of optic neuritis.

- Demyelination in the brain can cause symptoms of encephalitis such as confusion, memory issues and drowsiness.

- Spinal cord demyelination is referred to as ‘transverse myelitis’. Difficulty walking, changes in sensation to the limbs and difficulty with urination can occur with transverse myelitis.

What causes antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorders?

The exact cause of antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorders is not well understood. A dysfunction of the immune system causes the system to produce the abnormal antibodies; but it is unknown why the dysfunction occurs. Various theories include exposure to a virus, possible environmental triggers, and genetics.

Diagnosing antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory brain disease

Evaluating signs and symptoms

Your child’s medical history and current symptoms will be thoroughly explored. Your child’s health-care team will also complete a full physical exam including a complete neurological exam to see what particular signs of inflammation are present, for example movement abnormalities, talking difficulties, etc. They may also do a neurocognitive and psychiatric assessment, for example cognitive dysfunction, memory recall, etc. This will help in understanding what parts of the CNS are affected.

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an imaging procedure that uses radio waves and a large magnet to take pictures of the brain. An MRI provides the health-care team with information that cannot be obtained from an X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan with the added advantage of zero radiation exposure. MRI findings will vary depending on what antibody is in your child's brain. Classic MRI abnormalities are seen in neuromyelitis, but are often normal in anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Therefore, it is possible to have antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disease despite normal findings on MRI.

Blood test and lumbar puncture (spinal tap)

Your child’s health team will request a blood sample and a sample of your child's cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—the fluid that surrounds the brain and spine—to test for various inflammatory markers, proteins and auto-antibodies. It is important to test both the blood and CSF because the auto-antibodies may not always be present in the blood in the first stages of illness. Testing of the CSF is done by conducting a lumbar puncture, also called a spinal tap. The presence of neuronal auto-antibodies in the blood and/or CSF is critical to the diagnosis of antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory brain disease.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

An EEG measures the brain's electrical activity. Abnormalities in brain waves are indicative of changes in brain activity. EEGs are used over a period of time to measure improvements in brain activity and to assess how well the brain is working. This is often used in the diagnostic work-up in order to identify tangible changes in brain activity.

How is anti-NMDAR encephalitis diagnosed?

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is diagnosed with both a blood test and lumbar puncture. The antibody can be found in the blood and CSF. Other testing such as a MRI and an EEG are also completed to confirm diagnosis.

How is NMOSD diagnosed?

A blood test can identify the antibody that causes NMOSD, and a positive antibody confirms the diagnosis of NMOSD. Some patients can have a negative antibody test but still have symptoms and MRI evidence of NMOSD. These patients can be diagnosed as having NMOSD, but they are noted to be ‘antibody negative’. Other tests such as MRI, visual evoked potential (VEP) and other eye tests may also be completed to confirm diagnosis.

How is anti-MOG antibody encephalomyelitis diagnosed?

A blood test can detect this specific antibody. This antibody can cause a one-time occurrence of demyelination (a ‘monophasic’ event). In this instance, the antibody is initially positive at the time of the child’s symptoms, but can then become negative when re-tested months later. These patients may be generally well with no reoccurrence of demyelination symptoms.

Some patients continue to have positive anti-MOG antibody but no reoccurrence of symptoms after their first event. These patients are monitored to see if they will develop a second event of demyelination.

A third group of patients, who have a positive blood test at the time of presentation and continue to have positive anti-MOG antibodies on follow-up blood testing, may also continue to have episodes of demyelinating illnesses and symptoms. These patients require long-term immune suppression.

Treatment of antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory brain diseases

The primary treatment goals for antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory brain diseases are to:

- Control active inflammation

- Reduce disease-causing antibodies

- Treat and manage symptoms, such as seizures, with medications

The following treatments are the most commonly used.

Prednisone

Prednisone is a steroid drug that suppresses (turns off) various immune cells in the body. As a result, it plays a crucial role in preventing the inflammation associated with antibody-mediated reactions. Prednisone is usually one of the first-line medications used to treat neuroinflammatory disorders. Intravenous (IV) prednisone is given in large doses for 3-5 days to suppress inflammation. Sometimes, oral prednisone may be given for 3-4 months after the IV prednisone, to prevent the inflammation from re-occurring.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is an intravenously administered blood product that consists of pooled antibodies from hundreds of blood donors. IVIG is a protein that helps to boost your child’s own immune system to reduce CNS inflammation. IVIG is generally well tolerated. Infusion reactions are possible but can be reduced or stopped by medications such as anti-histamines.

Plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis is a blood filtration procedure, and it involves the removal of blood through a catheter placed in a patient’s vein. The blood is filtered so that the liquid portion called plasma, is separated from the cellular portion. The plasma containing inflammatory proteins and antibodies is removed, and the child’s healthy cells are separated and returned along with albumin (a donor blood product like plasma). This procedure is repeated for 5-7 times (cycles) usually every other day. Plasmapheresis works well to ‘wash out’ the inflammatory proteins causing inflammation in the body.

Rituximab

Rituximab is a biologic agent that targets B cells. B cells are the immune cells responsible for producing antibodies. Rituximab works by depleting your child’s B cells, inhibiting the production of auto-antibodies that are causing inflammation in the CNS. The old B cells are eventually replaced by a new, healthy population of B cells.

Rituximab is administered intravenously in the hospital over the course of several hours, also known as an infusion. Two doses are given two weeks apart, and the medication’s effect on the immune system can last six to nine months. Rituximab can be accompanied by some side effects during the infusion or shortly thereafter.

Other treatment options

It is important to note that not all patients will respond the exact same way to these treatments. Various factors impact the disease process as well as the response to treatment. Other treatments may also be added for control of symptoms and side effects such as anti-seizure medications, antibiotics and anti-psychotics.

How to prevent complications

Symptoms and complications of antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorders can be minimized by following the plan recommended by your child’s health-care team. This can include giving your child immune suppressive medications, performing regular blood testing and imaging, and making sure your child is regularly attending their medical appointments. Providing your child with a healthy balanced diet, adequate sleep and regular physical activity can also reduce the risk of relapses.

Complications

Children with antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorders may experience “flare-ups” or relapses of their condition, where symptoms of CNS inflammation reoccur. If your child has a relapse of their NMOSD, contact their health-care team so they may be assessed right away. Your child may need to be seen in the Emergency Department and have urgent imaging and testing.

Complications of anti-NMDAR encephalitis can include seizures or psychiatric symptoms that may continue for many years after the acute illness. Complications of NMOSD and anti-MOG antibody encephalomyelitis can include vision loss or motor or sensory symptoms in the limbs.

Helping your child

After your child has been diagnosed with an antibody-mediated neuroinflammatory disorder they may experience anger, sadness or anxiety. Receiving support or counseling many be helpful. A social worker or counselor can assist your child and family with coping with their diagnosis.

Your child may require additional assistance at home with their activities of daily living or may require additional support at school. Resources and supports can be put in place in the home or school as needed.

What about routine health visits?

Your child’s pediatrician or family doctor will continue to follow your child for routine health visits and if they are ill, for example if your child develops a sore throat.

What about vaccines?

Because many of the treatments for inflammatory brain disease suppress the immune system, it is very important that you ensure your child's immunizations are up-to-date. However, while on treatment, your child should not take any live vaccines. Live vaccines are immunizations that use an attenuated form of the microorganism to initiate an immune response. Examples include:

- MMR (measles, mumps, rubella)

- Chickenpox (Varicella)

- Oral influenza vaccine

The health-care team

Your child will be closely monitored by a neurologist who has experience with neuroinflammatory disorders and other members of the neurology team, including nurses and nurse practitioners. Your child may also be followed by other specialty teams such as ophthalmology, rheumatology or immunology.

Clinic visits

It is important to have your child regularly monitored, even if treatment is very successful and your child is feeling healthy. Your child may develop complications that are only mildly symptomatic or absent (asymptomatic) inflammation in the CNS that still require treatment. The health team will also need to monitor the potential effects of treatments by completing regular blood testing and MRI imaging.

At many paediatric hospitals, a child may continue to be followed by a paediatric neurologist until they are 18 years of age. When they turn 18, they will need adult care. Your child's neurologist will be able to tell you what to expect in terms of visits and how to transition to adult neurology care.

When to seek medical attention

Contact your child's neurology team, call 911 or go to the nearest Emergency Department right away if your child experiences any of the following:

- A seizure

- Changes in their level of consciousness

- Difficulty seeing

- Problems speaking or swallowing

- Balance issues