Chronic pain is common in young children (ages two to five) and can take many different forms. Examples include:

- pain in the musculoskeletal system (bones, muscles and tendons), often described as aching or soreness

- nerve-type pain, often described as tingling, burning or like an electric shock

- abdominal pain

- headaches

Over time, chronic pain can worsen through a “vicious cycle” of thoughts, feelings and behaviours about the pain itself. These factors may be different for each child.

The illustration below shows how the vicious cycle of pain can occur. There are several points along the cycle where you and your child’s health-care team can intervene to help your child manage their chronic pain so it does not become worse.

No medical test can tell us how much pain a young child is experiencing. Instead, we rely on a young child's behaviour and self-reporting (what they say about their own pain).

Assessing chronic pain at home

As a parent or caregiver, you play a crucial role in assessing if your young child is in pain. Watch for any changes in your child's behaviour and listen to what they say about their pain.

Behavioural signs of pain

- Pained facial expressions, such as grimacing or wincing

- Guarding or protecting part of the body

- Not following usual sleep or feeding routines

- Avoiding activities that are usually enjoyable, such as playing with toys, singing songs

- Avoiding outings or mixing with other children

- Avoiding physical activity that may provoke pain, such as walking, climbing stairs, hopping or jumping

- Regressing in development, for example needing help with dressing or bathing or wanting to sleep with a parent

Verbal signs of pain

Depending on your child's ability with language, they may also be able to express their pain with words.

- Very young children (such as two-year-olds) may use simple pain words such as "ouchie" or "boo boo" while pointing to or protecting the part of the body that is hurting.

- Through ages three and four, most children gradually learn to describe around four levels of pain intensity ("none", "a little", "some or medium" and "a lot").

- When a child is aged four or five years, they are even better able to express their pain verbally, but they might still confuse different types of hurt (for instance physical pain and hurt feelings).

It is important to separate the signs of physical pain and emotional distress, especially if your child is not yet verbal or has more limited language abilities. To see if your child's pain is mainly physical, watch for the behavioural signs listed above. To assess if your child is in distress, think about any recent events that may be affecting them, such as changes in their school, daycare or living arrangements, separation from a caregiver or illness or death of a family member.

| Even though it is important to recognize the difference between physical pain and emotional distress, it is also important to let children know that you believe their pain is real. |

Assessing chronic pain in medical settings

Chronic pain is complex. As a first step, several health-care professionals may be asked to see your child to check for any underlying causes of pain that could require treatment. If they do not find a specific cause, your child may be diagnosed with "chronic pain", which is a disease in its own right.

If your child is diagnosed with chronic pain, they may be seen by a health-care team that includes doctors, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists and physiotherapists. These health-care professionals will want to learn about your child's level of function – how much your child's pain disrupts their everyday movements and use of their body as well as their sleep, attendance at school or daycare, and their social or physical activities. They will also want to find out about the possible physical factors that affect your child's pain, such as poor strength, and any psychological factors, such as protectiveness or fear of further injury.

To get this information, the health-care team will:

- ask you or your child (if old enough) a number of questions

- use different assessment tools

Once your child's team understands these factors, they can better identify targeted treatments for your child's needs.

What would a doctor or nurse ask about?

- When and how the pain started, where it is located, what words would describe the pain, how strong the pain is

- Impact of pain on your child's sleep and school

- Any allergies or other conditions that your child might have or any conditions that run in the family

- If your child is taking medications for pain or other conditions

What would a psychologist ask about?

- Any changes in your child's behaviour and how much these reflect pain or emotional distress

- How your child's emotional state might be impacting their pain (for example frustration about missing a favourite activity, which could lead to muscle tension and, in turn, increased pain)

- Your child's behaviours and thoughts related to the pain (for example avoiding eating because of a tummy ache or thinking the pain will never go away)

- Which coping strategies you or your young child might already use

- How you as a parent or caregiver are responding to your young child's pain

In some cases, the symptoms of chronic pain can be amplified by psychological distress. The term for this is somatization.

What would a physiotherapist ask about?

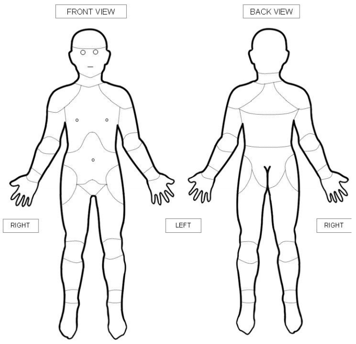

- Where in the body your child experiences pain

- How pain is limiting your child's physical activities

- Which physical treatment approaches your child has used in the past

Physiotherapists would also usually examine your child to assess their quality of movement, strength, range of motion and sensations (for example over-sensitive or under-sensitive to touch).

Assessment tools

Your child's health-care team will use a range of assessment tools to measure your child's pain.

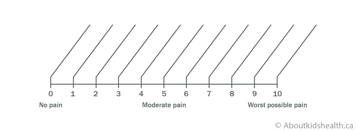

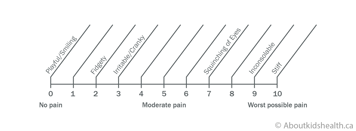

One tool that measures your child's behaviours is the Individualized Numeric Rating Scale (INRS). This tool is designed for young children who cannot yet use numbers or words to rate their pain. It asks parents to recall a time when they know their child was in pain to:

- describe the child's behaviours at that time (for example their facial expressions, level of activity and how easily they could be comforted)

- link those behaviours with a number from 0 to 10 (0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain imaginable)

When the behavioural information is filled in, a unique numerical pain scale is created for each child. Health-care professionals can refer to this scale to assess a young child's level of pain based on their behaviours. With repeated use, the scale can reveal changes in pain (if it is getting better or worse) over time.

Young children can also use tools such as body diagrams to report the location of their pain. By pointing at the diagram, the child can share where exactly they are feeling pain in their body.

Websites

Website designed to help children get control of their pain (German Paediatric Pain Centre)

http://www.deutsches-kinderschmerzzentrum.de/en/

Website where children can learn the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines the fun way https://www.participaction.com/the-science/benefits-and-guidelines/children-and-youth-age-5-to-17/

Videos

How does your brain respond to pain

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7wfDenj6CQ

Modules that explain how to understand pain, pain management and supporting youth https://mycarepath.ca/courses

Sesame Street song that teaches belly breathing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mZbzDOpylA

Content developed by Danielle Ruskin, PhD, CPsych, in collaboration with:

Anne Ayling Campos, BScPT, Fiona Campbell, BSc, MD, FRCA, Lisa Isaac, MD, FRCPC, Jennifer Tyrrell, RN, MN, CNeph

Hospital for Sick Children

References

Coakley, R., & Schechter, N. (2013). Chronic pain is like… The clinical use of analogy and metaphor in the treatment of chronic pain in children. Pediatric Pain Letter, 15(1), 1-8.

Coakley, R. (2016). When Your Child Hurts: Effective Strategies to Increase Comfort, Reduce Stress, and Break the Cycle of Chronic Pain. Yale University Press.

Carney, C., Carney, C.E., & Manber, R. (2009). Quiet Your Mind & Get to Sleep: Solutions to Insomnia for Those with Depression, Anxiety, Or Chronic Pain. New Harbinger Publications.

Mindell, J.A., & Owens, J.A. (2003). Sleep problems in pediatric practice: clinical issues for the pediatric nurse practitioner. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 17(6), 324-331.

Paruthi, S., Brooks, L.J., D'Ambrosio, C., Hall, W.A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R.M., ... & Rosen, C.L. (2016). Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785.

Ruskin, D., Amaria, K., Warnock, F., & McGrath, P. (2011). Assessment of pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Handbook of pain assessment, 213-241.

Stinson, J. N., Connelly, M., Jibb, L. A., Schanberg, L. E., Walco, G., Spiegel, L. R., Tse, S. M., Chalom, E. C., Chira, P., … Rapoff, M. (2012). Developing a standardized approach to the assessment of pain in children and youth presenting to pediatric rheumatology providers: a Delphi survey and consensus conference process followed by feasibility testing. Pediatric rheumatology online journal, 10(1), 7. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-10-7

Solodiuk, J., & Curley, M.A. (2003). Pain assessment in nonverbal children with severe cognitive impairments: the Individualized Numeric Rating Scale (INRS). Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 18(4), 295-299.

Valrie, C.R., Bromberg, M.H., Palermo, T., & Schanberg, L.E. (2013). A systematic review of sleep in pediatric pain populations. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP, 34(2), 120.