What is ataxia?

Ataxia is a movement disorder. Movement disorders are conditions that cause involuntary body movements. Uncontrolled movement starts in the brain, in the area you use to move, speak and pay attention. When children have ataxia, they have trouble controlling their muscles and can be clumsy and awkward.

What is Friedreich ataxia?

Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) is an inherited condition that causes loss of muscle coordination (ataxia), slurred speech (dysarthria), weakness and sensory loss. Symptoms usually begin between ages five and 15, with most diagnoses made before age 25. Occasionally, symptoms begin in adults over 30 or in children younger than five years of age. Although it is a rare disorder, FRDA is the most common form of inherited childhood onset ataxia, occurring in about 1 in 40,000 people. In some regions or ethnic groups, this number might be a little higher or lower. The time that it takes for FRDA to progress happens at different speeds in different children and can eventually impair day-to-day life.

Signs and symptoms of Friedreich ataxia

Children with FRDA may show some or all of the following signs and symptoms:

- Curvature of the spine (scoliosis) and foot deformities (high arches in the feet called “pes cavus”)

- Difficulty knowing where their hands and feet are in space (impaired position sense), leading to difficulties with balance and coordination

- Weakness in the legs and hands

- Mild to severe heart problems, such as thickening of the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy)

- Hearing loss

- Changes in vision

- Problems with bladder control

- Fatigue

- Difficulty speaking

- Diabetes

Friedreich ataxia is a genetic disease

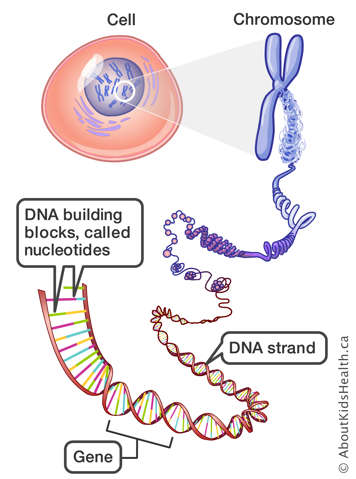

FRDA is an inherited condition, meaning it is passed from parents to their children through genes. Genes are the instructions that our cells use to make proteins. They tell our cells how to work and what to do. For example, one gene may determine the colour of your hair or your blood type. Each person carries two copies of each gene. A child gets (inherits) one copy from their mother and the other from their father.

FRDA is caused by the mutation of a gene called FXN, which makes a protein called frataxin. Normally, people have two working copies of the FXN gene. Children with FRDA have two non-working copies.

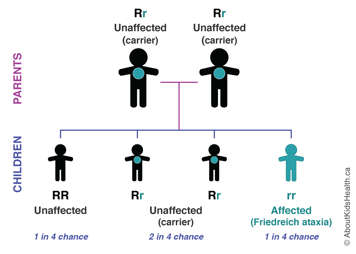

FRDA occurs in a child only if both parents are carriers; that is, if both parents carry one normal (working) version of the FXN gene and one mutated (non-working) version of the FXN gene. FRDA is a recessive condition, which means that both parents have passed down their mutated FXN gene to their child.

Most parents do not know that they carry the mutated FXN gene because they have only one copy of it. This makes them carriers of FRDA. They are unaffected and do not have any symptoms of the condtition. In fact, most carriers are unaware of their carrier status until they have a child with FRDA. If both carrier parents pass the mutated FXN gene to their child, that child will have FRDA. In each pregnancy, carrier couples have a one-in-four chance of having a child with FRDA, a one-in-two chance of having a child who is a carrier of FRDA, and a one-in-four chance of having a child who is not a carrier of FRDA nor has the condition.

For more information about genes, please see the AboutKidsHealth section on How the Body Works: Genetics.

Diagnosis

There are many types of mutations that can lead to genetic disorders. In the case of FRDA, the mutation comes from the addition of genetic material. The mutated FXN gene is much longer than the normal gene. A normal FXN gene contains a three base sequence (GAA) that is repeated five to 33 times in the DNA. These are the instructions for the body to produce the protein frataxin. The instructions for the mutated version of the FXN gene are much longer, and the sequence is repeated between 66 and 1700 times. This causes the gene to turn off, which stops the production of frataxin. Without frataxin, the nerves in the brain and spinal cord become damaged.

To confirm a diagnosis, children suspected of having FRDA can have a genetic blood test to determine whether or not they have the mutated gene. The test looks specifically at the FXN gene to determine if there is a mutation. Children with one normal FXN gene and 34 to 65 repeated sequences on the other gene are said to have a “premutation”. They do not show any symptoms of FRDA; however, there is an increased chance for the repeated sequence size to increase in their reproductive cells. This means that they are potential carriers of the disorder and could have a future child with FRDA. Children with 44 to 66 repeated sequences on one FXN gene may, develop FRDA later in life if the second copy of the gene is mutated.

In some cases, a child may have a different type of genetic mutation that also causes FRDA called a point mutation or “spelling mistake” in the FXN gene. Further testing may be needed if your child has this type of mutation.

Other tests that may help in the diagnosis of FRDA include the following:

- Electromyogram (EMG), a test for measuring the electrical activity of muscle cells

- Nerve conduction studies, tests measuring the speed of impulses transmitted by nerves

- Electrocardiogram (also called EKG or ECG), a test that measures the electrical activity of the heart

- Echocardiogram, a test using sound waves to take pictures of the heart

- Blood tests to check for elevated glucose levels and vitamin E levels

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans, tests that take pictures of the brain and spinal cord

Related conditions

Some other conditions that can look like FRDA include: ataxia with vitamin E deficiency; abetalipoproteinemia, Refsum disease; infantile onset spinocerebellar ataxia; ataxia-telangiectasia; and many others. A geneticist can help to make a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

There is currently no cure for FRDA, but there are symptom treatments that can help maintain optimal functioning for as long as possible. FRDA is managed by ensuring proper care is given to the systems of the body that can be affected by the condition. This includes regular follow-up with a neurologist, a cardiologist (to monitor for heart problems) and an endocrinologist (hormone specialist to monitor for diabetes). Children with scoliosis will also need to be monitored by an orthopedic surgeon. Some diabetes and heart complications can be managed with medications, and research suggests that taking antioxidants may also help with heart-related problems in FRDA.

Physiotherapy is recommended to help monitor and maintain range of motion, and to help design an appropriate exercise program. An occupational therapist can assist with alternative communication and walking aids, and they can also assess safety risks in the home.

These symptom treatments can help improve your child’s quality of life by reducing the severity of the complications associated with FRDA. To develop the best treatment plan for a child with FRDA, parents, doctors, teachers, therapists and other family members should work closely together in the best interest of the child.

Complications

FRDA is a progressive condition that breaks down the muscles and nerves of the body over time. It does not affect intelligence, and the rate of progression happens at different speeds in different children. Children with FRDA experience a loss of muscle coordination (ataxia) and feel off-balance when walking. They may have difficulty knowing where their hands and feet are in space, and may develop weakness in their legs and hands. Curvature of the spine (scoliosis), slurred speech, stiffness of the lower limbs, loss of joint sensation, loss of sensation in the legs and feet, and difficulty controlling bowel and bladder function may develop over time.

More than half of individuals with FRDA also have a heart condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This can be associated with an abnormal heart rhythm, so routine follow-up with a cardiologist is important. Some individuals with FRDA can develop diabetes, so regular screening through blood work is also important. Other features include vision changes and/or hearing loss.

Genetic counselling

Genetic counselling can help families adjust and cope with the stresses associated with having a child with FRDA. Prenatal testing can also be done during a pregnancy. If you or your child have tested positive for a mutation or have a family history of FRDA, you may want to talk to a genetic counsellor. A genetic counsellor will help interpret and review the genetic testing or options for prenatal diagnosis for future family planning.

Support

For some families, it is helpful to connect with others who are experiencing a similar medical condition. Before and after diagnosis, psychological counselling or participation in support groups is often beneficial for children with FRDA and their family members.

At SickKids

SickKids has a special multi-disciplinary clinic for children with FRDA and their families. The clinic takes place in the cardiology department, and it is staffed by a cardiologist, nurse practitioner, geneticist and genetic counsellor who have experience taking care of children with FRDA. Cardiac evaluations including EKG; echocardiograms and Holtor monitoring; a detailed neurological examination; assessment of quality of life and well-being; and bloodwork to screen for complications of FRDA, such as diabetes, are performed during each annual visit.

Resources

For more information on FRDA, visit the following websites:

Canada

Muscular Dystrophy Canada

www.muscle.ca

Ataxia Canada

www.lacaf.org

International

Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA)

www.curefa.org

euro-ataxia (European Federation of Hereditary Ataxias)

https://www.euroataxia.org/

Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA)

www.mdausa.org

National Ataxia Foundation

www.ataxia.org

References

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (2024, July). Friedreich's Ataxia Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/friedreich-ataxia

National Organization for Rare Disorders (2018). Rare Disease Database: Friedreich’s Ataxia. Retrieved from https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/friedreichs-ataxia/

Muscular Dystrophy Canada (2019). Types of Neuromuscular Disorders: Friedreich’s Ataxia. Retreived from http://www.muscle.ca/about-muscular-dystrophy/types-of-neuromuscular-disorders/

Ataxia Canada (2014, June). Cardiac problems in Friedreich’s Ataxia. Retreived from https://lacaf.org/en/cardiac-problems-in-friedreich-ataxia/

Corben LA, Lynch D, Pandolfo M, et al (2014). Consensus clinical management guidelines for Friedreich ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 9: 184.