There are two types of diabetes insipidus (DI):

- Central DI: Not enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is produced or released from the pituitary gland.

- Nephrogenic DI: The pituitary produces enough ADH, but the kidneys do not respond to ADH.

This article focuses on central DI.

What is hypopituitarism?

Hormones are chemicals produced in the body. They act as messengers that travel to other parts of the body where they affect how organs work. Hypopituitarism is a condition where the pituitary gland does not produce one or more pituitary hormones, or it does not produce enough hormones. "Hypo" means less than usual. The term "panhypopituitarism" means many or all of these hormones are deficient ("pan" means all).

The pituitary gland is a pea-sized gland located in the middle of the skull. It is part of the body’s endocrine system, which includes all of the glands that produce and regulate hormones. The pituitary gland acts as the control centre for other glands. Hormones produced in the pituitary gland impact many other parts of the body. The pituitary gland releases various hormones in response to chemical messages it receives from the part of the brain called the hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus is our "thirst centre" and senses when we need to drink. This helps ensure the body has enough water and does not become dehydrated.

What is antidiuretic hormone deficiency/diabetes insipidus?

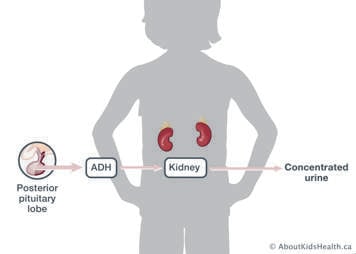

The hypothalamus produces a hormone called antidiuretic hormone (ADH), which is also called vasopressin. ADH helps the body retain water. It is stored and released from the back (or “posterior”) part of the pituitary gland. When ADH is released, the kidneys use it to concentrate urine to help retain the water that it needs to function properly.

When there is not enough ADH, the kidneys are unable to concentrate urine. The two most obvious warning signals are:

- excessive thirst

- frequent urination, often very dilute, pale-coloured urine

This can lead to severe dehydration if not enough fluids are taken to keep up with the amount of fluid being lost as urine. Infants and young children with ADH deficiency cannot easily satisfy their thirst and are especially at risk of dehydration. Children with this condition must always be allowed to drink enough water to satisfy their thirst so they do not become dehydrated. Children should drink according to their level of thirst—do not limit the amount of fluids in your child’s diet. The child’s school, day care, and/or babysitter needs to be aware of this. Severe dehydration requires immediate medical treatment. ADH deficiency is also called diabetes insipidus (DI). This condition has no relation to the more common condition of diabetes mellitus.

How is ADH deficiency/DI diagnosed?

Your child’s health-care provider may order the following tests to see if your child has ADH deficiency:

- urine tests: to see if urine can be concentrated (turn yellow in colour)

- blood tests: to check sodium levels

- water deprivation test: to observe if dehydration occurs if fluid intake is stopped

- MRI: images taken of the brain to check for pituitary abnormalities

How is ADH deficiency/DI treated?

Treatment of central DI may include replacement of ADH with DDAVP (vasopressin or desmopressin).

Desmopressin can be given as a nasal (nose) spray medication (called desmopressin spray), in pill form (called desmopressin or DDAVP), in a pill that dissolves under the tongue without the need for water (called DDAVP Melt), or as a subcutaneous (under the skin) injection. Desmopressin helps the body in the same way that ADH does, by holding in the fluid that the body needs.

The pill form of the medication can be stored at room temperature. However, the nasal spray and injections must be stored in the refrigerator. There are special instructions for how to open the DDAVP Melt pills. Your health-care team or pharmacist will teach you how to do this properly. Generally, desmopressin needs to be given at least once, and often several times, per day for your child’s entire life.

For infants who are diagnosed with ADH deficiency, a different oral medication called hydrochlorothiazide might be used instead of DDAVP for the first six to nine months of life. This is because the dosing of DDAVP in infants can be very tricky. Babies also cannot tell you when they are thirsty. For this reason, your health-care provider may ask you to accurately record any fluids the baby drinks (such as milk, water, food, juice) and the amount of fluids the baby puts out (e.g., weighing diapers on a scale). More consistent feeding and diaper changing schedules (such as every three to four hours) may also be needed. This, in combination with blood levels of sodium, can help your health-care provider find the right dose of medication. Occasionally, older children may also lack a sense of thirst. You may have to monitor urine output and give your child a fixed fluid amount every day as prescribed by your health-care provider.

It is important to know the signs of too little or too much ADH in both infants and children:

| Too little ADH (not enough desmopressin-DDAVP | Too much ADH (too much desmopressin-DDAVP) |

|---|---|

|

|

If any of the above are noted, changes in the dose of medication may be needed to avoid complications. If your child has too little ADH and does not receive treatment, it can lead to excessive urination, dehydration, increased sleepiness and eventually coma. If your child has received too much ADH and does not receive treatment, it can lead to decreased urine output, confusion, increased sleepiness and possibly seizures.

If your child has no sense of thirst, they will be given a daily total fluid intake (TFI) to drink every day. The amount of fluid needed is based on the amount of urine your child produces while on the DDAVP medication in order to balance the “ins” (fluid intake) with the “outs” (the amount of urine they produce). The fluids may have to be increased during times of illness or times when there is increased fluid loss through sweating (for example, hot weather, increased physical activity). This should be discussed with your endocrinology team. Sometimes, you may be asked to measure the urine output to ensure the ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ are balanced.

Levels of sodium are monitored through blood work. Increased sodium may be an indicator of dehydration.

If your child is having increased urination in between doses of DDAVP, please contact your endocrinology team as a DDAVP dose adjustment may be needed.

Illness management

Hypernatremia

If your child is unwell and/or has vomiting/diarrhea, or your child is unable to take their DDAVP or tolerate oral fluids, please bring your child to your nearest emergency department for assessment. Lack of fluid intake and/or lack of DDAVP can lead to your child becoming dehydrated with an increased sodium level; this is known as hypernatremia.

Symptoms of hypernatremia include:

- headaches

- fatigue or tiredness

- irritability and confusion

- dry mouth and lips

- nausea and reduced appetite

- cramps and/or muscle spasms

- increased heart rate

- severe hypernatremia may lead to seizures and coma

If hypernatremia is not recognized and treated, it can be life-threatening.

Hyponatremia

If your child has taken their DDAVP and then has an intake of fluid much higher than their normal TFI, or a reduced urine output, they may have an excess of fluid in their system. This can lead to a reduced sodium level; this is known as hyponatremia. Please reach out to your endocrinology team as this may require medical attention. If your child shows symptoms of hyponatremia, please bring them to your nearest emergency department for assessment.

Symptoms of hyponatremia include:

- nausea (without vomiting)

- confusion

- headaches

- severe hyponatremia may lead to vomiting, seizures, reduced levels of consciousness and cardiac arrest

If hyponatremia is not recognized and treated, it can be life-threatening.