The physical and emotional changes of puberty reflect a biological transition from childhood to adolescence and young adulthood. In girls, these changes are the result of gradually increasing levels of estrogen, a hormone produced primarily by the ovaries. The timing of puberty and this increase in estrogen varies widely between girls, however, it is important to be aware of situations where differences in this timing reflects an underlying problem.

The ovaries and uterus (womb) are organs located in the lower abdomen and are involved in hormone production, menstruation (periods) and reproduction.

The ovaries serve two main functions:

- they produce hormones that control puberty and sexual characteristics (breast development, body proportions, menstruation) and sexual function

- they contain eggs which are required for reproduction

Among girls treated for brain tumours, both functions have the potential to be compromised either as the result of the tumour itself, or, more commonly, as a result of treatment.

Therefore, monitoring a girl’s progress through puberty is an important component of her medical follow-up during and after treatment for a brain tumour.

What happens in the body during puberty?

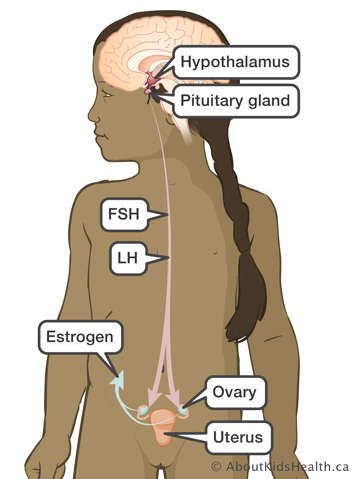

Puberty begins through a chain of events that start in the centre of the brain, in areas called the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The hypothalamus produces gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH). GnRH then triggers the pituitary gland to produce two hormones called follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH and LH trigger the ovaries to:

- Secrete estrogen (the principal hormone needed for female puberty)

- Allow eggs (ova) to mature and be released for fertilization.

The timing of puberty may be influenced by many factors including family patterns and medical conditions. Typically, puberty begins in girls with the onset of breast development between age 8 and 13 years. This is generally followed by the development of pubic hair, a growth spurt, changes in body proportions and finally, onset of menstrual periods.

How are puberty and fertility affected by brain tumours and treatment in girls?

Puberty

Girls treated for brain tumours may experience early puberty or delayed/absent puberty.

- The first sign of puberty is the development of breasts. If this occurs before age 8, it is considered early.

- The absence of breast development by age 13, or absence of menstrual periods (amenorrhea) by age 16 is considered delayed puberty.

Treatment for a brain tumour, with chemotherapy or radiation, can impair hormone production either by the brain or the ovaries. Radiation to the brain can impact release of GnRH, FSH and LH. Since FSH and LH stimulate the ovaries to trigger puberty and menstruation, their absence may result in failure of the ovaries to produce estrogen, which is needed to drive the changes of puberty and to undergo menstrual cycles.

The hypothalamus is more sensitive to radiation than the pituitary gland. If only the hypothalamus is injured (either by tumour, surgery or radiation), then puberty may come early. If both the hypothalamus and pituitary gland are impacted, then puberty may come late.

Chemotherapy or radiation may directly impact the ovaries. This too can affect their ability to make estrogen and, as with lack of LH and FSH, may delay the onset of puberty and menstruation.

Fertility

In addition to their role in producing hormones, the ovaries contain eggs (ova). Some chemotherapy drugs used in the treatment of brain tumours can reduce the number eggs in the ovaries. Radiation, when it involves the pelvis (such as craniospinal radiation), can also impact the egg count and integrity of the uterus. Depending on the type of therapy and the amount given, there may be few or no eggs remaining after treatment.

Thus, young women who were previously treated for brain tumours and who subsequently try to conceive, may have difficulty or be unable to become pregnant with their own eggs, or may be unable to carry a pregnancy in their uterus.

What are the specific causes of problems with puberty and fertility?

Several factors affect puberty or fertility by causing damage to the organs and cells involved in the normal progression of puberty and reproduction:

- Children who have germ cell tumours or a hypothalamic glioma may experience early puberty as a direct effect of the tumour. This is more common in children with neurofibromatosis (NF).

- Radiation therapy to parts of the brain called the hypothalamus and pituitary gland may affect their ability to produce hormones that are needed for puberty: GnRH, LH and FSH.

- Craniospinal radiation may have an impact when the radiation beam exits the body through the upper pelvis. In girls, the radiation beam may directly affect the uterus or ovaries.

Chemotherapy drugs, in particular, drugs called “alkylating agents”, may delay puberty and cause infertility. This category of drugs includes cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, lomustine (CCNU), carmustine (BCNU), procarbazine, busulfan and thiotepa.

How can problems with puberty and fertility be evaluated and treated?

During follow-up visits, the doctor or nurse-practitioner will assess for pubertal changes, such as breast development underarm and pubic hair. Growth and height will be recorded on a growth chart. Hormone levels may be checked by blood tests if early or late puberty is suspected.

Treatment for early (precocious) puberty

For early puberty, occasionally children are offered treatment with medications to slow down puberty. Depending on their age, this treatment may be suggested to prolong their period of growth since once puberty has finished, a child typically stops growing shortly thereafter. For girls, puberty may also be slowed down or stopped to avoid the onset of menstrual periods.

Children who experience early puberty may or may not benefit from pausing puberty. If the health-care team feels that a child would benefit from pausing puberty, a medication called depot leuprolide (Depot-Lupron) can be given by injection to slow down a child’s progression into puberty. This treatment is usually continued until the typical age of puberty.

Reasons to consider pausing puberty include:

- If the health-care team is concerned that going into puberty will cause impaired final height (i.e., that your daughter will be smaller than she would have been without treatment). Typically, if children enter puberty before age 6, this is a possibility, and there is evidence that pausing puberty may lead to increases in final height as an adult. When puberty begins after age 6, the evidence is less clear and a decision to pause puberty will need to consider multiple factors related to the goals of treatment, including a child’s current height, their bone maturation and parents’ heights.

- Starting puberty significantly earlier than peers can be emotionally challenging for some children and for their parents. For girls, beginning menstrual periods early can be particularly distressing. Concern about emotional impacts of early puberty can be a reasonable reason to pause puberty.

Decisions about pausing puberty will be made with the input of the child, caregivers, the primary oncology team and an endocrinologist, a doctor who specializes in treating disorders of hormone production and timing.

Treatment for late (delayed) or absent puberty

If there are no signs of puberty by an age where it would typically be expected (breast development by 13 years in girls) or if puberty starts but then fails to continue, this is referred to as delayed/absent puberty.

Delayed puberty or lack of menstrual periods is treated by taking estrogen, the hormone produced by the ovaries. Estrogen is most commonly taken as a pill every day. In addition to the external changes influenced by estrogen (breast growth, changes in body shape, etc.), it also influences bone strength, heart health and brain development.

Estrogen is initially given in small doses and this dose is increased gradually over a period of 2-3 years to mimic the pattern seen in children who undergo puberty spontaneously. This approach helps the child’s body change gradually and to achieve the most natural final appearance of the adult body. In girls, once the dose of estrogen approaches levels of an adult woman, a second hormone, progesterone, will be added to regulate menstrual bleeding. The two hormones may be taken together in a single pill, the combined hormonal contraceptive (also known as "the birth control pill").

Prevention, evaluation and treatment options for reduced fertility

Girls who need treatment with potential to affect fertility, may be offered a consultation with a gynaecologist, a doctor who specializes in female reproductive and sexual health, who can discuss evaluation for fertility as well as options for preservation of fertility, when they exist. There are no tests that can accurately determine the likelihood that a young woman may be able to become pregnant, although sometimes certain blood tests and ultrasound pictures of the ovaries and uterus may help in the evaluation.

Certain measures can be taken before cancer treatment to try to preserve fertility. One technique for girls undergoing craniospinal radiation is to locate the ovaries by ultrasound. If possible, an operation may be performed by a gynecologist to move one ovary out of the path of the radiation beam to protect it from damage.

Girls who have already started their periods may be eligible to freeze eggs prior to treatment. This is called oocyte (egg) cryopreservation and involves medical procedures (which some individuals might find intimate or challenging) and often a significant cost. More information about this approach may be found here. This may be discussed with the oncology team when cancer treatment is being planned. Oocyte cryopreservation may also be an option for girls after treatment, if it appears that some of the eggs have survived following chemotherapy.

New techniques to remove small parts of ovarian tissue for freezing and possible use later are being studied and developed and could be explored with your health-care provider if appropriate to your circumstances.

How will this affect your child’s future?

Children with early puberty may reach a shorter adult height if puberty is not slowed down or paused. Girls with early puberty may also experience early sexual attention from others, for which they may be emotionally unprepared.

Thus, it is important to have open conversations about appropriate (and inappropriate) attention and contact, with a clear plan of communication, should they experience any inappropriate sexual attention or contact.

Adolescents who are affected by delayed or absent puberty may need to remain on hormone therapy for life. In addition to maintaining sexual characteristics and sexual function, sex hormones (such as estrogen) are important to maintain bone strength and heart health. It may also be emotionally challenging for girls to mature significantly later than their peers or siblings, thus some may elect to begin puberty hormones to help address these concerns.Girls who underwent alkylating chemotherapy or radiation involving the ovaries (particularly during adolescence) are at risk for early menopause. The number of eggs decreases continually in females from birth until menopause and the overall number often decreases after chemotherapy. As a result, young women who have undergone chemotherapy are advised that chances of a successful pregnancy are much higher at younger ages (before age 30).

Egg freezing (oocyte cryopreservation) is also an option to be explored, particularly if there may be interest in delaying pregnancy until a more advanced age (over 30). Referral to a fertility specialist to discuss these options can be offered once a young woman has started having periods and is interested in engaging in this conversation.

For some young women, the treatments needed for cancer do not leave any surviving eggs. There are, however, many ways to build a family, including in-vitro fertilization (IVF) with donor eggs, surrogacy and adoption. These are options that the health-care team, potentially with the input of a fertility specialist, can discuss when the time is right.

Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines: Precocious Puberty after Cancer Treatment

Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines: Female Health Issues after Cancer Treatment