What is intestinal failure?

Intestinal failure is when the intestine (GI tract) cannot absorb the calories, fluids and nutrients your child needs for growth and day-to-day life.

The common causes of intestinal failure are:

- Short bowel syndrome: Occurs when a child is born with an intestine that is shorter than usual or when most of the intestine has been surgically removed. Part(s) of a child’s intestine may be taken out because of disease, poor circulation, infection, trauma or tumour.

- Digestive or absorption disorders: The entire intestine is present, but it cannot digest or absorb fluids and nutrients properly. Digestive or absorption disorders are usually rare genetic diseases, such as congenital diarrhea and enteropathies.

- Motility disorders: The intestine cannot contract its muscles normally to move food through the intestinal tract.

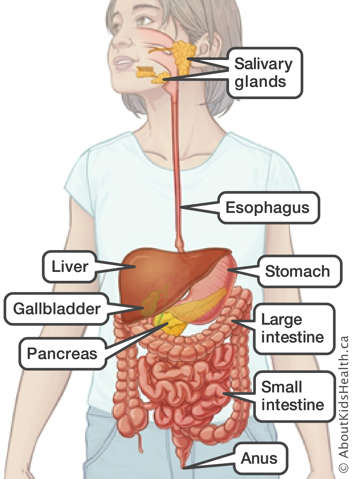

Understanding the gastrointestinal (GI) tract

The GI tract is divided in different parts and each part has its own function. Intestinal failure can affect one or more parts. The following are the parts of the GI tract that can be affected in intestinal failure.

Stomach

The stomach is a muscular pouch where food is mixed with gastric juices and breaks down into a smooth, soupy mixture called chyme. The chyme is then slowly released to the small intestine.

Small intestine

After food is broken down in the stomach, it passes into the small intestine. The small intestine is a long tube built of intestinal cells, muscle and nerves that digest, absorb and move food from the stomach toward the large intestine (colon).

The small intestine has three parts:

- duodenum

- jejunum

- ileum

The small intestine digests and absorbs most of the fluids and nutrients from food.

Large intestine

The large intestine, also called the colon, absorbs any fluid and electrolytes that were not already absorbed by the small intestine. The large intestine is also where stool is formed.

The large intestine has six parts:

- cecum

- ascending colon

- transverse colon

- descending colon

- sigmoid

- rectum

Liver

The liver is the largest abdominal organ and is connected to the bowel through the bile ducts. Functions of the liver include:

- producing bile that helps break down and absorb fat

- making factors that help blood to clot and prevent bleeding

- storing sugars like glycogen

- storing vitamins and minerals

- breaking down drugs and toxins and eliminating them from the body

- producing protein

- removing bacteria from the blood and helping to fight infection

For more information about the intestines, and to learn about other parts of the GI tract and how they work together to digest food, please see the GI tract page.

Signs and symptoms of intestinal failure

A child with intestinal failure may have the following signs and symptoms:

- dehydration without intravenous (IV) fluids

- very poor nutrition without IV nutrition

- poor tolerance of food by mouth or enteral tube

- constant and persistent diarrhea

- poor growth or weight loss

- no muscle strength or mass

- being very tired

- abdominal pain and/or distention

- vomiting or reflux (when food comes up from the stomach)

Assessment and diagnosis

If your child shows signs of intestinal failure, they will be assessed by an intestinal failure rehabilitation program (IRP). An IRP has the knowledge and expertise to complete the assessments needed to diagnose and treat intestinal failure. During the primary (first) assessment for intestinal failure, your child will have a variety of diagnostic tests, bloodwork and nutritional assessments to determine diagnosis and treatment.

Most children with intestinal failure are diagnosed as infants as the conditions that cause intestinal failure commonly occur and are identified in infancy.

Treatments

Total parenteral nutrition

When a child cannot absorb nutrients through their GI tract, a specialized form of food is given directly into the blood stream through the veins (intravenously), often a central venous access device (CVAD). This alternative to regular food is called total parenteral nutrition (TPN). TPN provides liquid nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals and electrolytes, as well as fluids.

Your child will need parenteral nutrition if their digestive system cannot absorb or tolerate enough food or fluids by mouth or through a feeding tube. TPN is usually given every day over 12 hours or more. In many cases, but not all, the amount and the frequency of TPN use decreases as children grow and better absorb their food.

Intestinal rehabilitation

Intestinal rehabilitation focuses on managing intestinal failure through diet, medications and surgery. This is done through intestinal rehabilitation programs.

The goals of intestinal rehabilitation are to:

- wean or reduce the use of TPN

- achieve enteral autonomy (this means your child receives all their nutrition and fluid through the digestive system, either by eating by mouth or G tube feeding when possible)

- prevent complications related to intestinal failure

- improve your child's and your family's quality of life

- achieve optimal cognitive and motor development

Treatment of intestinal failure is long and may take months or years, or sometimes may be lifelong. Many children can achieve enteral autonomy, but not everyone will. Whether your child achieves enteral autonomy depends on their disease and the length and function of their small and large intestines.

Intestinal transplant

Your child’s health-care team may consider intestinal transplant if your child has persistent intestinal failure that does not respond to standard therapy, which usually includes TPN, and develops severe complications related to intestinal failure or TPN.

Possible complications

There are several early and late complications that may occur due to intestinal failure and its treatment. Early complications may occur as a result of treatment. Late complications are typically caused by receiving nutrition in a different way than the body expects over a long period of time.

Early complications

IFALD: Intestinal failure–associated liver disease

Intestinal failure–associated liver disease (IFALD) occurs in intestinal failure for many reasons. The following are some of the factors that contribute to IFALD:

- blood infections

- prematurity

- absence of food through the GI system (also known as enteral feeds, which deliver food directly to the stomach or small intestine)

- the composition of the parental TPN (total parenteral nutrition; a way of providing liquid nutrients directly into the bloodstream)

Central line–associated blood infection (CLABSI)

A central venous access device (CVAD) is a special intravenous (IV) line that can be used to give medications and IV nutrition (TPN) directly into the bloodstream. Infection can occur if bacteria enter the bloodstream through the central line. Recurrent episodes can affect many parts of the body and have a significant impact on quality of life due to prolonged admissions in hospital.

Central line thrombosis

A central line thrombosis is a blood clot that occurs in the veins used for CVAD placement. If your child has had many clots, they may not have any more veins available to place a CVAD. If this occurs, your child may need an intestinal transplant to help them get the nutrients they need.

Some factors that contribute to thrombosis are the location of the central line, the size of the catheter and the development of CLABSI.

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO)

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) is an imbalance of bacteria in the small bowel. This is common in intestinal failure due to the changes in bowel anatomy in children with short bowel syndrome, repeated use of intravenous and oral antibiotics, altered feeding practices and use of acid reflux medication. SBBO can cause:

- inflammation

- malabsorption

- vitamin deficiencies

- bacteria to move from the bowel to other parts of the body, which can cause abdominal pain and distension

- inability to tolerate food

- metabolic acidosis (too much acid in the body, either because the body cannot balance the acid or is making too much acid)

- diarrhea

- dehydration

- weight loss

- recurrent infections

Late complications

Developmental issues

Children with intestinal failure may have developmental disabilities due to the following factors associated with the condition and its treatment:

- prematurity

- low birth weight

- central line complications

- being admitted to the hospital for long periods

- number of surgeries

- high bilirubin

It is important that your child have neurocognitive assessments as part of long-term follow-up with the IRP to ensure they receive the appropriate supports.

Metabolic bone disease

Metabolic bone disease is caused by changes in the way minerals are absorbed. Children with intestinal failure do not properly absorb minerals that are important to bone health, such as calcium, magnesium and phosphorus. Other factors that contribute to bone disease in children with intestinal failure include vitamin D deficiency, dehydration or loss of minerals (bicarbonate) in their stools.

Kidney disease

The effects of intestinal failure and using TPN over a long period of time can lead to kidney disease. Here are some of the factors that contribute to kidney disease in children with intestinal failure:

- persistent dehydration

- contaminated TPN solutions

- exposure to medications that are damaging to the kidneys, such as IV antibiotics

Micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies

Micronutrients include vitamins and minerals that are essential to many of the body’s functions, including bone health, growth and development. Children with intestinal failure have trouble absorbing vitamins and minerals, which can lead to low levels of micronutrients. Children can have deficiencies in micronutrients whether they are on or off TPN support.

At SickKids

At SickKids, the intestinal rehabilitation program is called the GIFT Program. The GIFT team will assess your child in order to diagnose and treat intestinal failure.