What is hereditary multiple osteochondromas?

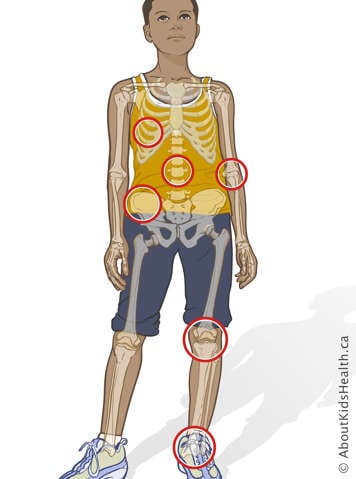

Hereditary multiple osteochondromas, or HMO, is a genetic condition that affects bone development. HMO affects about one in 50,000 people worldwide. Osteochondromas are bony growths that typically develop during childhood and adolescence. People with HMO develop these bony growths on the ends of long bones, such as the legs and arms, and on some flat bones, such as the shoulder blade (scapula) and the hip bones (pelvis).

How do hereditary multiple osteochondromas affects the body?

Bones

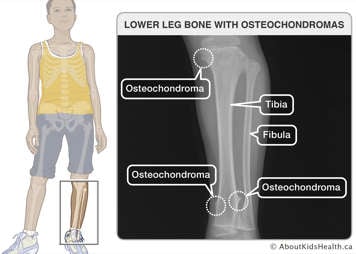

People with HMO have osteochondromas that grow on the surface of their bones, such as the long bones of the arms and legs, ribs, spinal column and hip bones. You can sometimes feel them under the skin, and they can sometimes be painful. The number and size of the osteochondromas vary from person to person and can be different even between family members (e.g., parent and child).

Height and body shape

Most people with HMO do not have noticeable physical differences. However, depending on the location and size of the osteochondromas, they can sometimes lead to shortening and bowing of long bones and joint problems. For example, shortening and bowing of the long bones in the lower limbs can cause one leg to be shorter than the other. People with HMO can be shorter than their predicted height, but most are still within the typical height range for their age. HMO does not affect intelligence.

HMO is a genetic condition

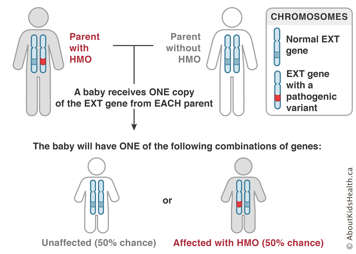

Genetic means related to genes. Each of us inherits our genes from our parents. Genes provide our bodies with instructions that influence our health, development, appearance and behaviour. In general, each person has two copies of every gene. One copy is inherited from each parent.

HMO occurs as a result of a genetic variant (also known as a pathogenic variant) in one copy of the EXT1 or the EXT2 gene.

- In about 10% of people with HMO, neither parent has the condition, and the genetic variant is new in the child, appearing for the first time.

- In about 90% of people with HMO, the variant is inherited (passed on) from one of the parents.

HMO is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition. This means that:

- Only one copy of the gene (either EXT1 or EXT2) has a genetic variant that prevents the gene from working properly, causing HMO. The other copy of the gene works normally but is not enough to prevent a person from having HMO.

- A person with HMO has a 50% chance during each pregnancy of passing this genetic condition on to the child.

- The risk to siblings of a person with HMO depends on whether the parent has HMO or not.

To learn more about genetics, please visit the genetic counselling article.

Course of the disease

The growth of the osteochondromas begins in early childhood. The average age of diagnosis is three years. Nearly all people with HMO are diagnosed before 12 years of age. As a child grows, new and existing osteochondromas can grow slowly over the years. Most of the time, osteochondromas stop growing after someone's bones have matured (i.e., after puberty). Most people with HMO lead active and healthy lives.

HMO can be diagnosed before or after birth

Before birth, HMO cannot be identified on prenatal ultrasound because the osteochondromas usually do not start growing until early childhood. However, HMO can be obtained from the pregnancy by either:

- chorionic villus sampling (CVS) between the 11th and 14th week of pregnancy or

- amniocentesis after the 15th week of pregnancy

Genetic testing for HMO during pregnancy can only be performed when there is a known genetic diagnosis of HMO in the family (e.g., if the parents have another child diagnosed with HMO or one of the parents has HMO). This means that the genetic variant responsible for causing HMO in the family must be known.

After birth, your doctor may suspect HMO based on specific characteristics of your child's bones and if there is a family history of the condition. The diagnosis of HMO can be made from X-ray findings and confirmed by DNA testing of the EXT1 and EXT2 genes (a blood test).

Treatment of HMO

There are no treatments to prevent the growth of osteochondromas. At this time, treatment is based on each person's symptoms. Children with HMO lead fulfilling lives when they receive attentive, informed care from their parents/caregivers and health-care providers.

Treatment of complications

Pain and discomfort

Some people with HMO develop pain associated with an osteochondroma. Depending on the size and location of the osteochondromas, they may cause compression of peripheral nerves and/or irritation of overlying muscles and tendons. This can cause pain, compress blood vessels and restrict joint motion.

Pain management, physical therapy and surgery are the treatment options available for the various complications.

- Pain should be managed with medication when needed, as directed by your health-care provider.

- Painful osteochondromas that result in compression of a nerve or blood vessel may be treated by surgery.

- If osteochondromas are large or if bone deformities occur, then surgical removal may be an option.

Monitoring for cancer

The most important aspect in HMO management is monitoring for cancer. The risk for an osteochondroma to become cancerous increases as a person ages (about a 2% to 5% risk over a person's lifetime). Monitoring the size of osteochondromas may help ensure early detection and treatment. For this reason, it is important to notify your health-care provider if your child begins to experience rapid growth of osteochondromas and increasing pain. It is especially important to speak to a health-care provider if this occurs during adulthood as osteochondromas are not expected to grow after puberty.

Treatment of malignant transformation (cancer)

If an osteochondroma becomes cancerous (chondrosarcoma), your child will need surgery to remove the osteochondroma. Their health-care team may consider using radiotherapy and chemotherapy in specific cases. Speak to your oncology team for more information about treatment.

Pregnancy and childbirth

Pelvic bone osteochondromas may cause problems in pregnancy and childbirth. Pregnant individuals with HMO may require a caesarean section if there is a large osteochondroma on the pelvis that may block the passage of a baby during delivery.

Genetic counselling for HMO

People with HMO and their families should consider assessment by a geneticist and genetic counsellor. Genetic counselling can help with the following:

- confirming the diagnosis

- discussing how the condition may affect your child over time

- evaluating the risk that future children will also have HMO

- discussing available options for managing the condition

Coping with HME

Because of the risk associated with osteochondromas, your child should avoid activities that increase this pain. These activities are different for every child. Encourage your child to participate in activities with other children the same age. As well, try to physically adapt your child's surroundings to support your child and encourage independence.

Children with HMO should be followed carefully by their primary health-care physician or orthopaedic surgeon. Speak to your health-care team (primary health-care physician, genetic counsellor, geneticist or orthopaedic surgeon) if you need help or if you are having trouble coping.

Patient resources

The following organizations and sites can offer more information, support, and contact with other affected individuals and their families.