Sometimes, babies are born with malformations somewhere along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. These malformations are rare. They can occur anywhere from the esophagus to the anus. Many of these conditions can be surgically treated.

Esophageal atresia and fistula

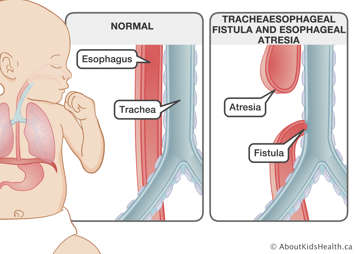

Esophageal atresia and fistula are malformations in which the natural breathing tube, known as the trachea, and the feeding tube, called the esophagus, are improperly formed. There are several types of these malformations, but, most often, the upper esophagus lacks a connection to the stomach while the lower esophagus connects to the trachea through an abnormal passage called a fistula. Babies with these types of malformations often need breathing support and nutrition. They are fed with total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or with a feeding tube directly into the stomach.

During this time, the baby gains strength, and the esophagus will continue to grow. After several weeks, the malformation is repaired with surgery.

Intestinal atresia

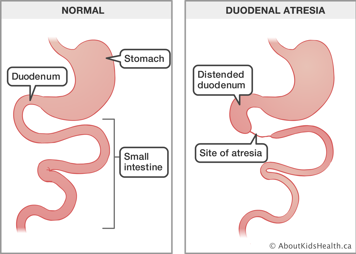

Intestinal atresias are malformations of the intestines in which a section of the intestines (bowel) is very narrow or is disconnected from the rest of the intestines. Most commonly, these occur in or near the duodenum, just past the stomach. Although atresias are rare, they are more common in babies born with Down syndrome. Babies with intestinal atresias are often small than other babies. Due to the narrowing or disconnection, babies with intestinal atresia often cannot digest their milk and vomit bile. Intestinal atresias are repaired with surgery.

Malrotation with volvulus

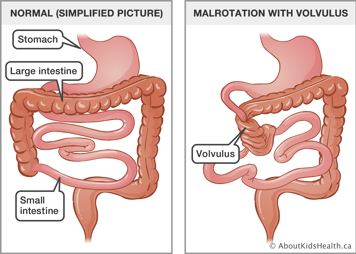

Until about the 10th week of pregnancy, a fetus’s GI tract develops, in part, in the umbilical cord. The GI tract then returns to the abdomen and rotates 90 degrees to the right. The GI tract rearranges itself and settles into a position that will then remain unchanged for the rest of a person’s life. At the end of this process, the GI tract is contained and supported in the abdomen and does not move.

Occasionally, this series of steps does not occur properly, and part of the GI tract, though still connected, ends up in the wrong place. This malrotation, as it is called, can remain loose and the intestines can move in many directions and become twisted. If the GI tract twists and loops around itself, the intestine can become blocked, and its blood supply can be affected. This is called volvulus. Malrotation with volvulus usually causes a baby to vomit bile and requires emergency surgery to correct the problem.

Hirschsprung’s disease

Hirschsprung’s disease is a condition in which nerve cells called ganglia have not formed on the inner wall of part of the rectum or large intestine. This causes the bowel to contract and not relax and leads to obstruction. Males are about 10 times more likely to have the disease than females. Babies with Hirschsprung's disease may be slow to pass meconium after birth and may have severe constipation from early infancy. Some can develop abdominal distention. Hirschsprung's disease is diagnosed with a contrast enema study, which is an X-ray series that looks at the large intestine, as well as a rectal biopsy, where a sample of the lining of the rectum is studied under a microscope to confirm the absence of ganglia.

Surgery, often performed in stages, is used to correct the malformation. Surgeons will identify the bowel section without ganglia, cut it out, and reattach the two ends of healthy bowel. Sometimes a colostomy, or the surgical removal of some of the bowels, is necessary, and the surgeons will do the final repair at six to 12 months of age.

Anorectal malformations

Some babies are born with malformations of the anus, rectum, or both. There are several general types. They have varying degrees of severity and are treated with surgery. The malformation can come in the form of:

- an absence of an opening where the anus should be

- a fistula, or small opening from the rectum to the urinary tract or to the vagina

- a variation of one of these categories

Depending on the exact nature and severity of the malformation, surgeons will close the fistula and, in the case of a missing anus, create an opening and gently pull though the bottom of the bowel, creating a new anus.