Your child's health-care team uses different methods and sources of information to assess your child's pain. These include pain scales, behavioural assessment tools and your child's pain history.

Pain scales and other measurement tools

Starting at about age three or four, children can reliably use pain scales, which will greatly improve the accuracy of an assessment. A child's self-reports (what the child says) will be viewed along with behavioural (how the child behaves) and physiological (how the child's body responds) indicators. Many of these pain-rating tools can reliably be used at home as well as the hospital.

If a child is not capable of self-reporting because of their age or condition, health-care providers will use behavioural and composite measures (those that combine behavioural, psychological and contextual indicators) to rate a child's pain. However, since only the child really knows how their pain feels, self-reports are the most important indicators of pain.

Self-report scales

Several self-reporting tools measure acute and chronic pain in children of different ages. Some measure a single aspect of pain, for example pain intensity. Others are more comprehensive or multi-dimensional and take into account the effect of pain on quality of life, for example through changes in mood, appetite and sleep.

Numerical/visual analogue scale (age three and older)

Generally, visual analogue scales consist of a 10 cm (4 inch) line labelled "No hurt" on the left and "Worst hurt" on the right. Numerical analogue scales are visual analogue scales with the numbers 0 to 10 in between. Children are asked to indicate their pain intensity by putting a mark on the scale that corresponds to their pain intensity (or how much they hurt). There are several variations you may see used during a pain assessment. For example, some scales are vertical and represent the concept of a pain thermometer. Other scales use colour increasing in intensity and have a slider for the child to move along the colour line. Visual analogue scales are designed to assess the intensity of pain only. Once the scale is explained to the child, they are asked to point to the place on the line that best represents how much pain they are feeling.

Faces scale (age three and older)

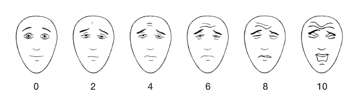

Generally, this type of scale shows five or six simple cartoon faces beginning with an emotionally neutral expression on the left, progressing to a very distressed and grimacing face on the right. As with visual analogue scales, the child is asked which face best represents how much pain they feel or, if used as a measure of fear and anxiety, which face that best represents how their pain feels.

An example is the Faces Pain Scale - Revised (FPS-R), shown below. The numbers are not shown to the child; these are for reference only. The FPS-R is available without charge for use by parents, clinicians and researchers at www.iasp-pain.org. A full-size image and instructions for administration of the scale are provided there in 25+ languages.

Faces Pain Scale - Revised. Copyright © 2001, International Association for the Study of Pain. Reproduced with permission. Source: Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford P, van Korlaar I, Goodenough, B.

The Faces Pain Scale - Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 2001;93:173-183.

Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ)

The PPQ, also called the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, is generally used for older children suffering from chronic pain. The questionnaire is focused more on how much pain is affecting a child's life rather than the nature and intensity of the pain itself. The PPQ is multi-dimensional and assesses the child's participation in activities and level of participation; how the pain has affected the child's emotional state and relationships; and how pain has affected the child's experience at school. There are also versions of the questionnaire for older children and adolescents.

Pain diary (age six and older)

A pain diary is a more complete record of pain. Children are asked to record not only their level of pain on a scale of zero to ten but also what they were doing when the pain began, what helped relieve the pain, and how long it took for the pain to go away. A pain diary can be a useful tool when the child's pain is unexplained or if the child is suffering from recurring pain. The additional information may provide clues to the source of the pain and how to better treat the pain. New versions of pain diaries are being developed and electronic versions may soon be available.

Drawings (all ages)

A child's own drawings can be one of the best ways of communicating their pain. Often a drawing provides an indication of the intensity of pain and can provide information on the type of pain the child is feeling. A drawing is also a useful starting point for discussion with the child to help them understand their pain and to reveal more details about it.

Behavioural measures for pain assessment

Faces, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC)

FLACC relies on behavioural indicators to assess pain. This tool is a checklist that guides the health-care professional in examining the child's behaviour in response to pain. This checklist was developed for children aged two to seven years for use after surgery or when experiencing sharp, acute pain during a procedure.

The FLACC scale

| Face | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 - No particular expression or smile | 1 - Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested | 2 - Frequent to constant frown, clenched jaw, quivering chin |

| Legs | ||

| 0 - Normal position or relaxed | 1 - Uneasy, restless, tense | 2 - Kicking or legs drawn up |

| Activity | ||

| 0 - Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily | 1 - Squirming, shifting back/forth, tense | 2 - Arched, rigid, or jerking |

| Cry | ||

| 0 - No cry, awake or asleep | 1 - Moans or whimpers, occasional complaint | 2 - Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints |

| Consolability | ||

| 0 - Content, relaxed | 1 - Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or "talking to," distractible | 2 - Difficult to console or comfort |

How to use the FLACC scale

- Rate child on each of the five categories (face, legs, arms, crying, consolability). Each category is scored on the 0 to 2 scale.

- Add the scores together (for a total possible score of 0 to 10).

- Document the total pain score.

In children who are awake: Observe for 1-5 minutes or longer. Observe legs and body uncovered. Reposition child or observe activity. Assess body for tenseness and tone. Console the child if needed.

In children who are asleep: Observe for 5 minutes or longer. Observe body and legs uncovered. If possible, reposition the child. Touch the body and assess the tenseness and tone.

Interpreting the score

| 0 = | Relaxed and comfortable |

|---|---|

| 1–3 = | Mild discomfort |

| 4–6 = | Moderate pain |

| 7–10 = | Severe pain or discomfort or both |

Composite measures for pain assessment

Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP)

PIPP is a comprehensive assessment tool used for newborn babies born either at term or pre-term. A preterm, also called premature baby, is born before 37 weeks gestation. A newborn infant's pain intensity is determined by measuring three behavioural indicators (facial expressions) and two physiological indicators (heart rate and level of oxygen), and considering them along with two contextual indicators (the child's gestational age at birth as well as their sleep/wake state). These seven indicators are scored together to provide an indication of acute pain.

The PIPP scale can be found in: Stevens B, Johnston C, Petryshen P, Taddio A. The premature infant pain profile: Development and initial validation. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 1996;12(1):13-22.

Scoring instructions for PIPP scale

The PIPP scores range from 0 to 3 in each of the seven pain indicators. The scores obtained for the seven indicators are summed for a total pain score.

The maximum attainable score is dependent on gestational age and behavioural state (since they influence responses). For extremely premature newborns in quiet sleep states, the total possible score is 21, as gestational age and sleep state are each assigned a score of three. In contrast, newborns greater than 36 weeks gestation are assigned a score of zero for gestational age. Therefore, the maximum possible PIPP score for the most mature premature newborn, even during sleep states, is 18. Scores of less than six usually indicate no pain or minor pain while scores greater than 12 usually indicate moderate to severe pain that require some pain management.

Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist

This checklist has been designed to help parents and caregivers identify clues that may indicate pain in children who suffer from autism or brain disorders from severe illness or injury. These children may have daily pain due to stomach reflux or spasms from stiff joints. The parents are asked to indicate how often each item on the scale is observed in their child (not at all, just a little, fairly often, very often). Items include activities like moving and jumping around and body positions such as "flinches or moves away part of body that hurts." Since children recovering from surgery will not be able to communicate their pain if they have any, a post-operative version of this checklist is also available.

Download post-operative pain checklist [PDF]

Download non-communicating pain checklist [PDF]

These checklists appear courtesy of Lynn Breau, PhD.

Pain history

A detailed history will be part of any pain assessment. If your child cannot provide information about their pain history because of age, disability, or incapacity, the history will be obtained from the parents. In most situations, a pain history will be obtained from both the child and the parents.

Collecting your child's history is very important because it helps health-care providers understand how your child is coping with their pain. How much pain is felt is often influenced by emotion and temperament and your child's previous experience with pain. By obtaining an accurate history, health-care professionals will get a sense of how your child thinks and feels about pain and how these thoughts and emotions are influencing how they are expressing their current pain. A history will also reveal what words, such as "hurt," your child uses to express pain. Your child may be asked what kind of pain they have had in the past and how they have coped with it. You and your child will also be asked what pain medications have been taken before, if they worked, and if they produced side effects such as nausea or vomiting. You will also be asked what other pain relief methods you may have used to help your child, such as heat or cold or the use of distraction.

Your child's beliefs and past emotional experiences around pain can influence how they express pain. Since these beliefs are formed within a family, social and cultural context, an inquiry into these aspects of your child's life may also make up a part of the pain history. For example, your child may be asked if they believe that showing pain is a sign of weakness. As a parent, you may be asked what effect pain has had on your child including play, sleep, appetite, mood, school and relationships with family members and others.