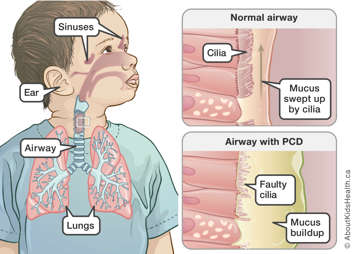

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) occurs when a child inherits a gene mutation that prevents their cilia from moving properly (see below).

Cilia are tiny hair-like structures along the respiratory tract that sweep constantly to clear mucus from the lining of the lungs, ears and sinuses. Once the mucus reaches the upper airway, it can be coughed up or swallowed.

When someone has PCD, their cilia do not move as they should. This means that the mucus that would normally be swept out of the respiratory tract collects in the airways. Trapped mucus carries dirt and bacteria that can cause repeated infections of the respiratory tract, including the lungs, ears and sinuses.

PCD is a chronic (long-lasting) disease that needs routine follow-up with different health-care professionals. However, with treatment and regular follow-up, most children with PCD have a good quality of life.

PCD and other organ systems

About half of all people with PCD also have situs inversus totalis. This occurs when the organs in the chest and abdomen are reversed; for example, the heart and stomach are on the right and the liver is on the left. In most cases, this abnormal organ placement is not harmful.

However, a small minority of people with PCD have organ abnormalities that might affect their functioning and health. These can include congenital heart defects (heart defects from birth), polysplenia (multiple spleens) or asplenia (no spleen).

The most common symptoms of primary ciliary dyskinesia are:

- recurring ear infections and/or hearing loss

- a long-lasting “wet” cough from birth or infancy, with or without mucus

- recurring chest infections

- wheezing that does not respond to asthma therapy

- nasal congestion, thick nasal drainage or chronic nose infections

- sinus congestion or sinus infections.

Symptoms usually occur in early childhood, although not everyone who inherits PCD has the same symptoms.

If symptoms occur in newborns, the first sign of difficulty might be breathing difficulties shortly after birth with a need for oxygen or respiratory support for no clear reason.

Recognizing symptoms early

It is important to recognize the possible symptoms of PCD early, as this will help your child get a prompt diagnosis. Children with a delayed diagnosis of PCD can experience stigma at school because of symptoms, such as a cough.

It is also worth explaining to teachers that PCD is not contagious — your child cannot spread it to anyone else. However, if another child has PCD or cystic fibrosis, infections could spread more easily between them. In these situations, children should be separated into different classrooms if possible.

How is PCD inherited?

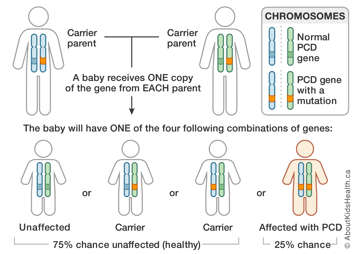

PCD is a recessive genetic condition. To develop it, a child must inherit two gene mutations, one from each parent.

In the example in this image, each parent has one PCD gene mutation. This makes them "carriers" — they have the mutation, but they do not have any PCD symptoms. Most parents in this group do not know that they are carriers.

Two carriers have a:

- 25 per cent chance of having a child with PCD

- 50 per cent chance of having a child who is a carrier

- 25 per cent chance of having a child who does not have PCD and is not a carrier

In other words, their children may inherit two, one or no copies of the PCD gene mutation, as shown.

If a child inherits a PCD gene mutation from only one parent, they will also be a carrier but will not have PCD. If a child inherits two gene mutations, they will have PCD.

The risk of having a child with PCD is the same with each pregnancy.

How common is PCD?

PCD occurs in about one in every 15,000 children worldwide. It is more common in people of South Asian descent, where it occurs in about one in every 2,000 children.

How is PCD diagnosed?

The symptoms of PCD can mimic those of common childhood illnesses. This can often delay a clear diagnosis of the condition.

If your child has repeated ear, sinus or chest infections, it is very important that their paediatrician take a careful medical history. If they suspect that your child has primary ciliary dyskinesia, they should refer your child to a paediatric respirologist or a paediatric PCD clinic for specific tests.

Tests to confirm a suspected case of PCD

Your child may have a number of tests to check for PCD.

- A ciliary biopsy involves removing a small sample of cilia from the lining of the nose or airway and, with a special microscope, looking for proteins that help cilia move normally. If the proteins are missing, it could indicate PCD. This test is available only in specialized PCD clinics and is typically one of the first tests performed.

- For children aged five or older, a nasal nitric oxide test measures the level of a gas called nitric oxide in the air that your child breathes out from their nose. People with PCD have very low levels of nitric oxide in their nasal airway. The test is also available only in specialized PCD clinics.

- A blood test can check for the gene mutations that cause PCD. This test does not always provide definitive results, so your child might still need future genetic testing as more information about the genetic mutations that cause PCD are discovered.

How is PCD treated?

There is no cure for PCD, but most children with the condition can have a good quality of life with appropriate treatment and regular follow-up. The type of treatment your child receives depends on their PCD symptoms.

Treating the lungs

Chest physiotherapy (also known as airway clearance) is the main method to help loosen and clear a build-up of lung secretions (mucus).

- For babies and young children, a physiotherapist may teach percussion (tapping or clapping) on the chest in different positions twice a day.

- For older children, a physiotherapist may teach positive expiratory pressure (PEP) techniques using different devices.

Your child may also receive a suitable exercise program to help clear their lungs.

If your child has a lung infection, they may receive antibiotics orally (by mouth) or through a mask, to breathe in. Sometimes, a child may need to be admitted to hospital to receive intense physiotherapy and intravenous antibiotics (antibiotics through a vein).

Occasionally, even with the best of care, PCD may lead to severe lung disease that needs more intense treatment. For example, a child might need oxygen treatment at night or during exercise.

For an individual with very severe PCD (their lungs failing badly) doctors might suggest that they be assessed for a lung transplant. If a need for a lung transplant arises, it is usually not until mid or late adulthood.

Treating the ears and sinuses

If your child’s PCD-related sinus and ear problems are difficult to manage, they might need to see an ear, nose and throat (ENT) doctor. The doctor may recommend nasal rinses to clean the nose and sinuses or even surgery to more thoroughly clean out the sinuses.

Some doctors recommend inserting tubes to drain the ear passages. This is called a myringotomy procedure. This procedure can improve hearing and make it easier to treat any ear infection with a topical antibiotic such as ear drops.

Some children might need hearing aids to improve their hearing. To prevent speech and language delay, it is important to treat hearing loss as early as possible.

To avoid infection, children with PCD should:

- take reasonable infection control precautions such as washing hands frequently, particularly before eating and avoiding contact with people with a cold or illness

- stay up to date with routine scheduled immunizations (shots), including the pneumococcal vaccine and the yearly flu vaccine. You can arrange to get these shots at your family doctor’s office.

People with PCD can experience a number of complications because of their symptoms.

- Repeated ear infections can, over time, put your child at risk of hearing loss. They may also delay speech and language abilities in young children.

- Recurring chest infections can lead to bronchiectasis, a type of lung damage that allows mucus and bacteria to build up.

Activity

Children with PCD are encouraged to play games and exercise regularly to the best of their ability.

Activities such as running and swimming are often helpful because they help clear the lungs of mucus. Your child may also benefit from other forms of exercise.

What type of follow-up care does my child need?

Your child will have a check-up every three to four months at a PCD clinic. The health-care team at the clinic will review your child’s overall health and functioning and offer treatment and support to manage PCD symptoms.

Review of symptoms

Your child's health-care team will:

- monitor your child’s lung function (breathing)

- test your child’s sputum (mucus and saliva) for any harmful bacteria

- test your child’s hearing, about once a year

- do a chest x-ray and CT scan in case of ongoing chest problems.

Managing symptoms

If your child has any mucus build-up or signs of infection at the time of their follow-up appointment, they may receive:

- chest physiotherapy to clear their airways

- antibiotics (intravenously or by mouth), usually at a higher dose and for two to three weeks

- inhaled medications to help clear mucus.

Transition to adult care

During their regular check-ups, older children and teens will receive support to help them transition to the adult health-care system. They will have a chance to meet with the health-care team on their own to encourage their learning and independence. This includes understanding their PCD, the medications they are taking, how to refill their medication and how to book appointments. Teens may also receive genetic counselling to help with their own family planning in the future.

When should I seek medical attention?

See a family doctor if your child has:

- a fever

- increased coughing above baseline level for more than a week

- more mucus than in their typical ‘wet’ cough

- blood in their mucus

- ear pain and/or drainage.

The Hospital for Sick Children at: Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Clinic.

For more information and support regarding PCD

Visit:

- PCD Foundation

Genetic Disorders of Mucociliary Clearance Consortium

A network of nine North American centres that are collaborating in the diagnostic testing, genetic studies and clinical trials in patients with impairments in mucociliary clearance, focusing particularly on individuals with PCD.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

A source of information about PCD as well as the latest research on the condition across North America.

A source of consumer-friendly information about the effects of genetic variation on human health.

Shapiro AJ, Zariwala MA, Ferkol T, et al. (2016). Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of primary ciliary dyskinesia: PCD foundation consensus recommendations based on state of the art review. Pediatric Pulmonology, 51(2):115-132. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23304.