How is ventricular septal defect treated?

VSDs occur in a range of sizes and their treatment is very individual. Small holes may need no treatment. They often do not cause symptoms and may close on their own. Babies with symptoms caused by a VSD may need medication and increased calories to control symptoms and improve weight gain.

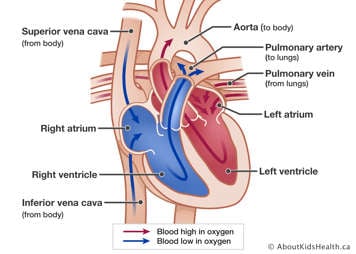

Children with large VSDs who have congestive heart failure are most likely to require surgery to repair and close the VSD. This is done during open heart surgery by applying a patch over the hole. Sometimes, a closure device can be inserted through cardiac catheterization.

If there are several holes, the cardiologist may insert a band around the pulmonary artery, in a procedure called pulmonary artery banding. This allows the baby to grow until the child is better prepared for surgery to close the holes.