Chronic pain:

- lasts longer than expected (more than three months)

- can be continuous (never goes away) or recurring (comes and goes)

- persists even after regular healing times for injuries and illness have passed

Chronic pain can be a symptom linked with a disease, for example chronic joint pain in the case of arthritis. Other times, it can occur on its own and be a disease in its own right with specific diagnoses (such as fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, migraine) and treatments.

| Because pain is invisible, it is very important to let your child know that you believe their pain is real. |

The age of the child also plays a role in defining chronic pain. For example, if a two-month-old infant has been in pain since birth, health care professionals will likely define that as chronic pain.

Over time, chronic pain can become a disease in and of itself. Unlike the warning signal of acute pain, chronic pain messages no longer serve a purpose. The nerves continue to respond with a pain signal when there is no apparent reason for a signal at all.

Chronic pain can subdivided into chronic non-malignant pain, and cancer pain. Chronic non-malignant pain may begin as an acute pain such as following surgery or trauma, may occur in association with a disease such as arthritis or sickle cell disease, and may sometimes occur for no obvious reason.

For more details about cancer pain and recurrent pain, see Other Types of Pain

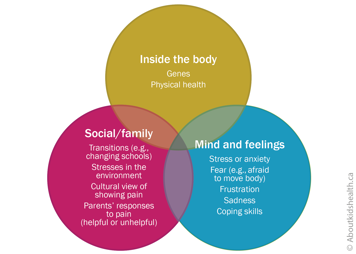

Children suffering from chronic pain may have varying amounts of disability, from mild to severe with impact on sleep, mood, school attendance, hobbies, sports and social isolation. The degree of disability may be independent of the amount of tissue damage and perceived severity of pain. Biological, psychological, social, cultural, and developmental factors can strongly influence the severity of chronic pain and the amount of disability it may cause.

Because there are many components to chronic pain, effective management may require different kinds of treatment. A combination of medication, psychological, and physical techniques may be used to manage the pain.

Why do some people have chronic pain?

We feel pain through pain pathways that travel between the body and the brain.

When someone has a healthy nervous system, their brain can tell the difference between movement and pain, for instance.

Some people begin to experience pain after a minor injury or illness, but then it persists long after they have healed. This happens when the nervous system continues to signal pain even though the initial injury has already healed (like a fire alarm ringing after the fire has been put out).

How does chronic pain develop?

Chronic pain can develop due to a number of related factors, such as:

- your child's physical health

- how much your child’s pain becomes a focus of attention for them and the rest of the family

- your child’s individual response to pain (say, if they protect the painful area or avoid painful activities)

- your child’s moods

- how others respond to your child with pain

These factors may be different for each child, with some factors being more or less important than others. As a result, chronic pain can vary widely from one child to another.

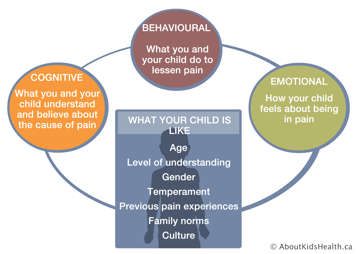

A number of factors also affect a child's experience of chronic pain. These include your child's age, gender, previous experience with pain and what they, and you, think, do or feel about the pain they have in the moment.

Because of this, pain is assessed and treated differently in infants and toddlers, young children, older children and teens.

Websites

Website designed to help children get control of their pain (German Paediatric Pain Centre)

http://www.deutsches-kinderschmerzzentrum.de/en/

Website where children can learn the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines the fun way https://www.participaction.com/

Videos

How does your brain respond to pain

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7wfDenj6CQ

Seven video mini-series on chronic pain and its management for youth (Pain Bytes)

http://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/chronic-pain/painbytes

Content developed by Danielle Ruskin, PhD, CPsych, in collaboration with:

Anne Ayling Campos, BScPT, Fiona Campbell, BSc, MD, FRCA, Lisa Isaac, MD, FRCPC, Jennifer Tyrrell, RN, MN, CNeph

Hospital for Sick Children

References

Coakley, R., & Schechter, N. (2013). Chronic pain is like… The clinical use of analogy and metaphor in the treatment of chronic pain in children. Pediatric Pain Letter, 15(1), 1-8.

Coakley, R. (2016). When Your Child Hurts: Effective Strategies to Increase Comfort, Reduce Stress, and Break the Cycle of Chronic Pain. Yale University Press.

Carney, C., Carney, C.E., & Manber, R. (2009). Quiet Your Mind & Get to Sleep: Solutions to Insomnia for Those with Depression, Anxiety, Or Chronic Pain. New Harbinger Publications.

Mayo Clinic Health System: Pathways through persistent pain: Tips for managing chronic pain (https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/8-tips-for-managing-chronic-pain)

Mindell, J.A., & Owens, J. A. (2003). Sleep problems in pediatric practice: clinical issues for the pediatric nurse practitioner. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 17(6), 324-331.

Paruthi, S., Brooks, L.J., D'Ambrosio, C., Hall, W.A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R.M., ... & Rosen, C.L. (2016). Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785.

Valrie, C. R., Bromberg, M. H., Palermo, T., & Schanberg, L. E. (2013). A systematic review of sleep in pediatric pain populations. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP, 34(2), 120.