Chronic pain affects one in five children. In older children (ages six to 12), it can take many different forms, including:

- pain in the musculo

- skeletal system (bones, muscles and tendons), often described as aching or soreness

- nerve-type pain, often described as tingling, burning or like an electric shock

- abdominal pain

- headaches

Over time, chronic pain can worsen through a “vicious cycle” of thoughts, feelings and behaviours about the pain itself. These factors may be different for each child.

The illustration below shows how the vicious cycle of pain can occur. There are several points along the cycle where you and your child’s health-care team can intervene to help your child manage their chronic pain so it does not become worse.

No medical test can tell us how much pain a child is experiencing. Instead, we rely on an older child's self-reporting (what they say about their own pain) and behaviour.

Assessing chronic pain at home

Verbal signs of pain

Children vary in how they express their pain. Between ages six and 12, some children will complain about their pain directly but others may also be able to localize (pinpoint) the pain in their body.

Behavioural signs of pain

- Avoiding school

- Avoiding hopping, jumping, stair-climbing, walking or other physical activities that might provoke pain

- Reducing participation in school sports

- Regressing, for example needing help dressing and bathing, or wanting to sleep with a parent

Disruptions in routines

- Your child may withdraw from hanging out with their friends.

- Your child's sleep schedule may be interrupted.

These changes might only be episodic (occurring from time to time). For example, your child may "overdo it" one day and then miss school the next because their muscles are not used to the level of activity your child had before the onset of their pain.

Assessing chronic pain in medical settings

Chronic pain is complex. As a first step, several health-care professionals may be asked to see your child to check for any underlying causes of pain that could require treatment. If they do not find a specific cause, your child may be diagnosed with "chronic pain", which is a disease in its own right.

If your child is diagnosed with chronic pain, they may be seen by a specialist health-care team that includes doctors, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists and physiotherapists. These health-care professionals will want to learn about your child's level of function – how much your child's pain disrupts their everyday movements and use of their body for different tasks as well as their sleep, attendance at school and their social or physical activities. They will also want to find out the possible physical factors that affect your child's pain, such as poor strength, and any psychological factors, such as protectiveness or fear of further injury.

To get this information, the health-care team will:

- ask your child a number of questions

- use different assessment tools

Once your child's team understands these factors, they can better identify targeted treatments for your child's needs.

What would a doctor or nurse ask about?

- When and how the pain started, where it is located, what words would describe the pain, how strong the pain is

- The impact of the pain on your child's sleep and schooling

- Any allergies or other conditions that your child might have or any conditions that run in the family

- If your child is taking medications for pain or other conditions

What would a psychologist ask about?

- Any changes in your child's behaviour and how much these reflect pain or emotional distress

- How your child's emotional state might be impacting their pain (for example frustration about missing a favourite activity, which could lead to muscle tension and, in turn, increased pain)

- Your child's behaviours and thoughts related to the pain (for example avoiding eating because of a tummy ache or thinking the pain will never go away)

- Which coping strategies you or your young child might already use

- How you as a parent or caregiver are responding to your child's pain

In some cases, the symptoms of chronic pain can be amplified by psychological distress. The term for this is somatization.

What would a physiotherapist ask about?

- Where in the body your child experiences pain

- How pain is limiting your child's physical activities

- Which physical treatment approaches your child has used in the past (see below)

Physiotherapists would also usually examine your child to assess their quality of movement, strength, range of motion and sensations (for example over-sensitive or under-sensitive to touch).

Assessment tools

Your child's health-care team will also use various tools to measure your child's pain.

Some tools look at behaviours (such as facial expressions, level of activity, how easily your child can be comforted). Other tools ask children to rate their pain using different scales, for example 0-10, small vs. medium vs. a lot or according to a series of pictures of faces in pain. With repeated use, these scales not only pinpoint the level of pain reported by the child but also reveal if the pain is changing (getting better or worse) over time.

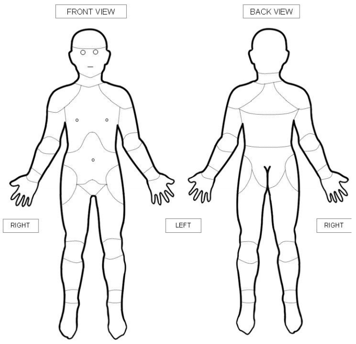

Older children can also use tools such as body diagrams to report the location of their pain. By pointing at the diagram, they can share exactly where they are feeling pain in their body.

Websites

Website designed to help children get control of their pain (German Paediatric Pain Centre)

http://www.deutsches-kinderschmerzzentrum.de/en/

Website where children can learn the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines the fun way

http://buildyourbestday.participaction.com/en-ca/tutorial

Videos

How does your brain respond to pain

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7wfDenj6CQ

Seven video mini-series on chronic pain and its management for youth (Pain Bytes)

http://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/chronic-pain/painbytes

Modules to understand pain

https://mycarepath.ca/understanding-pain

Modules for pain management

https://mycarepath.ca/pain-management

Content developed by Danielle Ruskin, PhD, CPsych, in collaboration with:

Anne Ayling Campos, BScPT, Fiona Campbell, BSc, MD, FRCA, Lisa Isaac, MD, FRCPC, Jennifer Tyrrell, RN, MN, CNeph

Hospital for Sick Children

References

Coakley, R., & Schechter, N. (2013). Chronic pain is like… The clinical use of analogy and metaphor in the treatment of chronic pain in children. Pediatric Pain Letter, 15(1), 1-8.

Coakley, R. (2016). When Your Child Hurts: Effective Strategies to Increase Comfort, Reduce Stress, and Break the Cycle of Chronic Pain. Yale University Press.

Carney, C., Carney, C.E., & Manber, R. (2009). Quiet Your Mind & Get to Sleep: Solutions to Insomnia for Those with Depression, Anxiety, Or Chronic Pain. New Harbinger Publications.

Mayo Clinic: Tips for Managing Chronic Pain (https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/8-tips-for-managing-chronic-pain)

Mindell, J.A., & Owens, J. A. (2003). Sleep problems in pediatric practice: clinical issues for the pediatric nurse practitioner. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 17(6), 324-331.

Paruthi, S., Brooks, L.J., D'Ambrosio, C., Hall, W.A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R.M., ... & Rosen, C.L. (2016). Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785.

Stinson, J. N., Connelly, M., Jibb, L. A., Schanberg, L. E., Walco, G., Spiegel, L. R., Tse, S. M., Chalom, E. C., Chira, P., … Rapoff, M. (2012). Developing a standardized approach to the assessment of pain in children and youth presenting to pediatric rheumatology providers: a Delphi survey and consensus conference process followed by feasibility testing. Pediatric rheumatology online journal, 10(1), 7. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-10-7

Valrie, C. R., Bromberg, M. H., Palermo, T., & Schanberg, L. E. (2013). A systematic review of sleep in pediatric pain populations. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP, 34(2), 120.