What causes acute pain in young children?

In young children (ages two to five), acute pain is typically caused by:

- routine vaccinations by needle

- earaches and sore throats

- everyday bumps and bruises

- injuries when learning how to walk, run and climb

- dental treatments (such as cavity fillings)

- procedures such as blood work, lumbar punctures or intravenous starts

- surgeries (operations)

- complex health conditions (such as cancer)

Pain affects children differently. If your young child is undergoing a procedure that you would find painful, they are likely experiencing at least as much pain as you would experience. Indeed, certain procedures may be more painful for young children because their brains cannot yet help them cope with pain, for example through distraction or thinking positive coping thoughts.

At this age, it is hard for children to clearly tell the difference between distress from emotions (for example fear) and distress from pain when they experience procedures such as a needle poke. Research has shown that preschoolers who are more distressed before getting a needle express more pain right afterwards.

Never discount your young child's pain-related distress even if you feel that their injury or procedure would not be painful for you.

Assessing acute pain at home

You play an important role in recognizing if your young child is in pain. Watch for any changes in your child's behaviour and listen to what they say about their pain.

Behavioural signs of acute pain

These include:

- muscle tension or stiffness

- squirming

- arching the back

- pained facial expressions (for example frowning, jaw clenching or grimacing)

- drawing up the legs or kicking

- guarding or protecting the painful area

Verbal and vocal signs of acute pain

Verbal and vocal signs include whimpering, moaning or sobbing or sometimes being extra quiet or not wanting to talk. Depending on your child's ability with language, they may also be able to express their pain with words.

- Very young children (such as two-year-olds) may use simple words such as "ouchie" to express pain. They may also point to or protect a certain part of the body to show that it is hurting.

- Through ages three and four, most children gradually learn to understand and describe around four levels of pain intensity ("none", "a little", "some" or "medium" and "a lot").

When a child is aged four or five years, they are even better able to express their pain verbally. They might still confuse different types of hurt (for instance physical pain and hurt feelings), but that does not mean they do not have pain. They are learning and you need to help them understand different types of pain.

Assessing acute pain in medical settings

In medical settings, such as the hospital, health-care professionals will work with you and your child to find the best way for your child to talk about their pain.

In a younger child, the health-care team will assess pain by looking at their behaviours as outlined above.

Some young children might be afraid to speak up about their pain for fear that they will get a needle or a medication that makes them feel sick. At first, it might be hard for young children to understand that painful procedures can make their pain better (for instance receiving pain medication through a needle). But you may encourage your child to talk about their pain without fear if you clearly explain why it is important for them to express pain and remind them about their positive experience with a painful procedure in the past.

Depending on your child's age and maturity, children around the age of four may be able to describe their pain using hands-on tools. With the Poker Chip Tool, for instance, caregivers can offer young children four poker chips and tell them each poker chip is a "piece of hurt". The more poker chips the child takes, the more pain they are feeling.

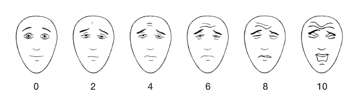

Some children as young as five can use pain scales such as the Faces Pain Scale - Revised to rate the intensity of their pain.

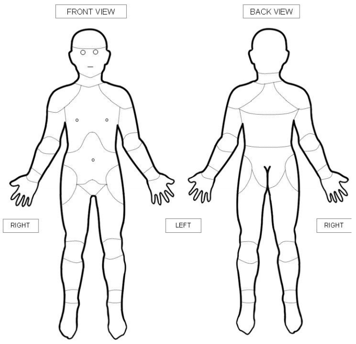

Other children at the upper end of this age group may be able to point to parts of their body or to body diagrams to show exactly where the pain is occurring.

However, until a child is aged six or seven, you as their parent or caregiver would still need to help them report their pain and whether it is getting better or worse over time.

Factors that affect pain assessment

A developmental disability or intellectual disability may make it difficult for your child to express their pain in words. In this case, their health-care team will use standard pain assessment tools to look at their behaviour. One such tool is the NCCPC, which helps make caregivers more aware if a child's behaviour may be different than usual due to pain.

Gender can affect how children express pain and how accurately their pain might be assessed. For instance, small boys will cry, but older boys may put a lot of effort into making sure they do not, especially if others are around. On the other hand, young girls may cry more because this behaviour is deemed more acceptable in certain cultures. Or, the reverse could occur.

Cultural differences can also account for a wide variety of reactions to situations. Some cultures may express themselves freely, but others may repress their emotions or respond to pain in unexpected ways. Some children may adopt the role of a "good patient" and behave the way they believe health-care professionals want them to behave rather than express how they are feeling.

How you can help health-care professionals understand your child's pain

Whether you are at home or in the hospital, you are the expert on your child's behaviour. Learn to understand the ways your young child shows and says they are in pain and share this with your child's health-care providers.

Be sensitive to your child's pain and whether a procedure might be painful for them. For instance, help your child be heard when they are in pain and ask your health-care professionals ahead of time if an upcoming test might be painful.

When you are prepared for a painful procedure, you are calmer and better able to cope. This will help limit the pain and distress of your young child before, during and after the procedure.

All children should be encouraged to express truthfully how much pain they are feeling so that health-care providers can give the most accurate assessment and recommend the most appropriate treatment.

Websites

Jokes to help distract toddlers and preschoolers

https://kidsactivitiesblog.com/24447/jokes-for-kids/

Preparing your child with cancer for painful procedures

https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/children/preparing-your-child-medical-procedures

Faces Pain Scale - Revised

https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1519

Videos

Pain management at SickKids

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_9_OQFo2APA

Reducing the pain of vaccination in children (2 mins 18 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgBwVSYqfps

Reducing the pain of vaccination in children (20 mins 52 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=TGGDLhmqH8I

Learning how to manage pain from medical procedures (Stanford Children's Health) (12 mins 58 secs)

https://youtu.be/UbK9FFoAcvs

Content developed by Rebecca Pillai Riddell, PhD, CPsych, OUCH Lab, York University, Toronto, in collaboration with:

Lorraine Bird, MScN, CNS, Fiona Campbell, BSc, MD, FRCA, Bonnie Stevens, RN, PhD, FAAN, FCAHS, Anna Taddio, BScPhm, PhD

Hospital for Sick Children

References

Blount, R. L., Cohen, L. L., Frank, N. C., Bachanas, P. J., Smith, A. J., Manimala, M. R., & Pate, J. T. (1997). The Child-Adult Medical Procedure Interaction Scale–Revised: An assessment of validity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(1), 73-88.

Campbell, L., DiLorenzo, M., Atkinson, N., & Riddell, R. P. (2017a). Systematic Review: A Systematic Review of the Interrelationships Among Children's Coping Responses, Children's Coping Outcomes, and Parent Cognitive-Affective, Behavioral, and Contextual Variables in the Needle-Related Procedures Context. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(6), 611–621. https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy/article/42/6/611/3073481

Campbell, L., Riddell, R. P., Cribbie, R., Garfield, H., & Greenberg, S. (2017b). Preschool children's coping responses and outcomes in the vaccination context: Child and caregiver transactional and longitudinal relationships. Pain.https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001092

Hicks, C.L., von Baeyer, C.L., Spafford, P., van Korlaar, I., Goodenough, B. (2001). The Faces Pain Scale - Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 2001;93:173-183.

Merkel, S., Voepel-Lewis, T., Shayevitz, J. R., & Malviya, S. (1997). The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs, 23, 293-7.

Taddio A., McMurtry, C. M., Shah, V., Pillai Riddell, R. et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2015. DOI:10.1503 /cmaj.150391

Uman, L.S., Birnie, K.A., Noel, M., Parker, J.A., Chambers, C.T., McGrath, P.J., Kisely, S.R. (2013) Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005179.pub3

von Baeyer, C.L., Jaaniste, T., Vo, H.L.T., Brunsdon, G., Lao, AH-C, Champion, G.D. Systematic review of self-report measures of pain intensity in 3- and 4-year-old children: Bridging a period of rapid cognitive development. Journal of Pain, 2017;18(9):1017-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.03.005.