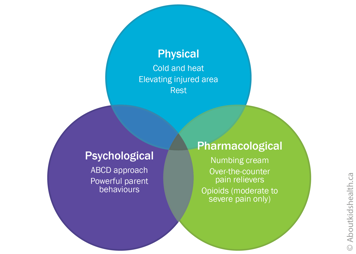

There is a lot that you can do as a parent to help your young child in acute pain. The most effective way to manage pain is with a combination of psychological, physical and pharmacological (medications) strategies, or methods. Together, these are termed the 3Ps of pain control. Like three legs of a stool, the 3Ps are complementary, or supportive, to one another.

No single strategy will likely be the answer for your child's pain. Your health-care professional can help you decide which combination might work best for your child.

Psychological strategies

One helpful way to soothe your young child in pain is to use the ABCD approach. Parents have reported that it is easy to understand and a recent study shows that it helps to reduce pain in toddlers but can also work for young children up to age five. If your child's pain is moderate or severe, you can easily combine the ABCD approach with pharmacological strategies.

ABCD approach

A: Assess your own anxiety

When you are calm, your young child is calmer and less likely to be distressed after a painful procedure or other cause of acute pain.

B: Belly breathe if you are stressed

Take a few calm and deep breaths down into your belly. This slows your own breathing and heart rate, which, if you are holding your young child in your arms, will also slow down their heart rate and breathing. When young children are in a parent's arms, parental heartbeats and breathing can help them feel less distressed before a painful procedure. Young children who are less distressed before a needle feel less pain afterwards.

C: Use a calm, close cuddle with your young child

Close physical contact between a parent and child can reduce a child's pain-related distress.

During a procedure, your young child may want to:

- stand between your legs while you are seated

- sit on an examining table in your arms

- have you massage their head while they are lying down

Think about what your child would want and work out a way to keep them close to you while allowing the health-care professional to do their work.

D: Distract your young child

Distraction when your child's peak distress has passed (about 30 to 45 seconds after a needle, once their crying dies down) can also help ease your child's pain. Toys, bubbles, books and songs are all good ways to distract very young children. If your child is a preschooler, you may want to ask them about something fun that is coming up or ask how hard they can squeeze your hand. Some children may also like to get a sticker after a painful procedure.

If you notice that distraction is making your young child more distressed, go back to cuddling. An extra 60 seconds of cuddling can do a lot to help your child calm down and become more open to distraction from their pain.

Do not feel that you have to be there during a painful procedure. For example, if the sight of a blood test makes you very nervous or unwell, it may be best to leave the room and let the health-care team support your child. Do not feel ashamed by this; it is not unusual. When the test is over, you can come back in to give hugs and cuddles. A young child knows when a parent is distressed, so it is best to save them from any increase in their own anxiety.

Powerful parent behaviours

What you say, and do not say, can also help your young child cope with pain. In fact, research has shown that not saying the "wrong" things is more helpful for your child than saying the "right" things! The guidelines below have been shown to be very helpful.

- Do not reassure. It might sound strange, but it is better not to reassure your child when they are distressed. Telling a child "It's ok" or "You are fine" over and over when they know they are obviously not fine (scared, crying, screaming) can actually make your child more stressed.

- Do not criticize. Do not use your child's experience of pain to try to improve their behaviour or tell them they can do better. Saying things such as "Brave girls don't cry", "Your brother didn't cry this much" or "This needle isn't that big a deal" makes children more upset, which leads to more pain.

- Do not apologize. It is not your fault that your child is having a medical procedure, so do not say sorry for it or their pain. Some researchers believe that apologizing to your young child tells them that you are distressed. This in turn will make them more distressed.

- Do not give your young child choices during a procedure. Young children tend to be overwhelmed by an upcoming painful procedure, so do not ask them right beforehand what side they would like the needle, for example. If they need to have the same painful procedure again, you can ask them what they would like well ahead of time.

- Do tell the truth. If your child asks if a procedure is going to hurt, and you think it will, let them know it will but that it will be over soon. Tell them that scientists have shown that kids who are less upset before a needle show less pain after a needle.

Physical strategies

Cold and heat

If your child has any swelling or other signs of inflammation, it can be helpful to apply cold (such as a wrapped ice pack) to the area. This not only reduces signs of inflammation but can also help control pain.

About 24 to 28 hours after an acute (sudden) injury, it can be helpful to apply heat (for example with a heating pad or a hot water bottle).

Be careful to avoid injury with heat and cold packs. Only apply them for short periods at a time (say, 10 minutes on/10 minutes off) and monitor the area closely. Your child should be able to move the heat or cold pack away on their own or tell you if it is uncomfortable.

Elevating the injured area

If your child has pain and swelling after an acute injury, it can be helpful to elevate (raise) the painful body part to a level above their heart. Elevating a painful arm or leg, for instance on a pillow while your child lies down, allows any excess fluid to drain. This in turn reduces pressure and pain in the injured area.

Resting or modifying movement

If your young child injures themselves, it is often a good idea to rest the injured area or at least modify (change) any essential movements. This gives the injured area time to heal and protects it from further damage.

Be sure to talk to a health-care professional first because complete inactivity may sometimes increase swelling in the area and/or lead to loss of motion and muscle strength.

Pharmacological strategies (medications)

Pain medications can also manage your young child's acute pain. They often come in different forms but for younger children, liquids are often preferred. Work with your young child to figure out the best way to give them liquids such as spoons, medicine cups or syringes.

Below is an outline of some common medications for acute pain. Because they treat different types of acute pain, some of them may be used together, if directed by your child's health-care team.

Always talk to a health-care professional before you use pain medications, especially if you are not sure which medication to use or which form of medication might work best for your child. They can advise you if a pain medication is safe and effective for your child's type of pain.

Numbing creams

Numbing creams can be helpful for painful needle-related procedures such as vaccinations or blood tests. Apply the cream to the area where the needle will be injected 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure. Ask for directions from your pharmacist or health-care team.

Over-the-counter medications

It may also be helpful for your child to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen before or after a painful procedure. Taking it 30 to 40 minutes before a procedure is sometimes recommended.

These medications can often last four to eight hours, so can be particularly good for acute pain such as an earache or pain after an injury.

Opioid medications

Opioids are among the strongest pain relievers and are often used after surgery or other major painful procedures. If your infant is in moderate to severe pain, their health-care team may prescribe opioids such as morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone, generally for short-term use.

| Opioids have risks and side effects, which can be serious. Always talk to your child's health-care provider for advice on taking, storing and disposing of opioids safely. |

Websites

Jokes to help distract toddlers and preschoolers

https://kidsactivitiesblog.com/24447/jokes-for-kids/

Preparing your child with cancer for painful procedures

https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/children/preparing-your-child-medical-procedures

Faces Pain Scale - Revised

https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1519

Videos

Pain management at SickKids

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_9_OQFo2APA

Reducing the pain of vaccination in children (2 mins 18 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgBwVSYqfps

Reducing the pain of vaccination in children (20 mins 52 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=TGGDLhmqH8I

Learning how to manage pain from medical procedures (Stanford Children's Health) (12 mins 58 secs)

https://youtu.be/UbK9FFoAcvs

Content developed by Rebecca Pillai Riddell, PhD, CPsych, OUCH Lab, York University, Toronto, in collaboration with:

Lorraine Bird, MScN, CNS, Fiona Campbell, BSc, MD, FRCA, Bonnie Stevens, RN, PhD, FAAN, FCAHS, Anna Taddio, BScPhm, PhD

Hospital for Sick Children

References

Blount, R. L., Cohen, L. L., Frank, N. C., Bachanas, P. J., Smith, A. J., Manimala, M. R., & Pate, J. T. (1997). The Child-Adult Medical Procedure Interaction Scale–Revised: An assessment of validity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(1), 73-88.

Campbell, L., DiLorenzo, M., Atkinson, N., & Riddell, R. P. (2017a). Systematic Review: A Systematic Review of the Interrelationships Among Children's Coping Responses, Children's Coping Outcomes, and Parent Cognitive-Affective, Behavioral, and Contextual Variables in the Needle-Related Procedures Context. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(6), 611–621. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx054

Campbell, L., Riddell, R. P., Cribbie, R., Garfield, H., & Greenberg, S. (2017b). Preschool children's coping responses and outcomes in the vaccination context: Child and caregiver transactional and longitudinal relationships. Pain. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001092

Merkel, S., Voepel-Lewis, T., Shayevitz, J. R., & Malviya, S. (1997). The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs, 23, 293-7.

Taddio A., McMurtry, C. M., Shah, V., Pillai Riddell, R. et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2015. DOI:10.1503 /cmaj.150391

Uman, L.S., Birnie, K.A., Noel, M., Parker, J.A., Chambers, C.T., McGrath, P.J., Kisely, S.R. (2013) Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005179.pub3

von Baeyer, C.L., Jaaniste, T., Vo, H.L.T., Brunsdon, G., Lao, AH-C, Champion, G.D. Systematic review of self-report measures of pain intensity in 3- and 4-year-old children: Bridging a period of rapid cognitive development.;Journal of Pain, 2017;18(9):1017-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.03.005.